The War On Tenor

How the ideological reframing of the murder of Maxwell Confait demonstrates the power of style guides and policy capture.

Updated 28/06/2023, see end

In 1972, Maxwell Confait, a 26-year-old gay man, was found dead in a locked bedroom after the fire brigade were called to a house fire in Catford, London. A subsequent autopsy revealed he had been strangled before the start of the blaze.

Three local boys were charged with his murder after confessing during police interrogation, despite an absence of physical evidence. All three later retracted their confessions, which they claimed had been coerced, but at trial all were convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment.

These convictions were overturned on appeal in 1975 after the court ruled their confessions had been improperly obtained. A report by Sir Henry Fisher in 1977 did not accept there had been any major impropriety by the police and concluded that two of the boys were probably guilty after all. In 1980, another suspect was identified, and the Home Office cleared the boys completely.

The case is regarded as one of the great miscarriages of justice, and had a profound impact on the British justice system, ultimately leading to the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984. This established stricter guidelines for police interrogations - especially for minors - including the requirement that all interviews be recorded.

In 2006, an article about this event was added to Wikipedia broadly covering the narrative outlined above, and describing Maxwell at one point as “a homosexual prostitute and transvestite who preferred to use the name "Michelle".” For 13 years this article was incrementally improved, expanded, copyedited, in fairly standard and uncontroversial ways.

In April 2019, however, this article was rewritten from an IP Address in Canada to favour the name “Michelle” and refer to Maxwell as “she” throughout, as well as referring to him as “queer”.

On January 8th 2022, this article was added to the category “Violence Against Women In London”.

In February 2023, a discussion was raised to move the article to “The Murder of Michelle Confait”. Despite objections, this was successful and the article was moved. It was reverted a few days later, but is now again in June 2023 being discussed for move, along with a call on the Gender Studies project to pull in more like-minded editors.

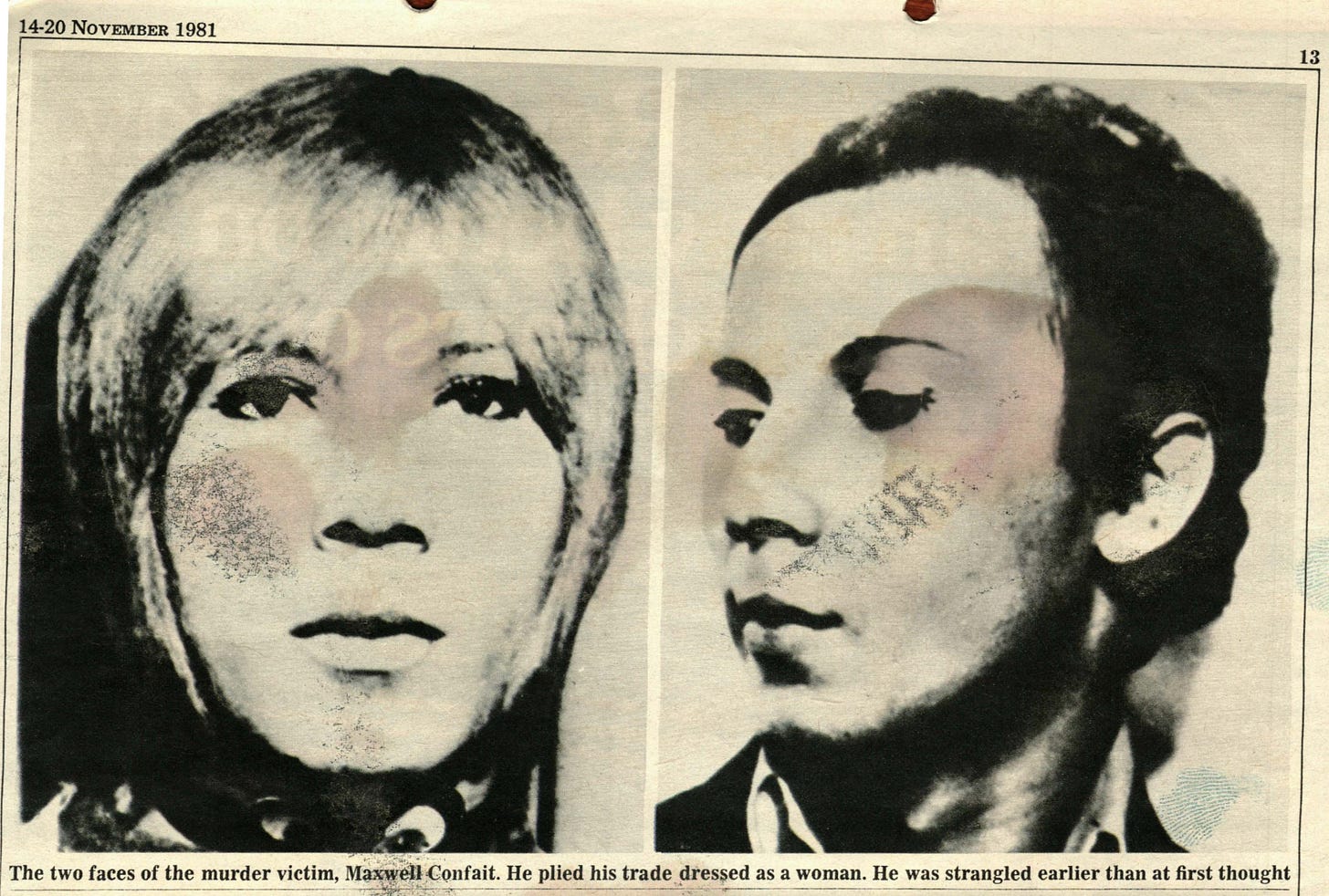

I’m quite convinced that much of this is taking place with the best of intentions, but it is clear that the murder of a gay man in London in 1972 and subsequent police mishandling of the case is being used fifty years later to advance a political agenda by regarding him as a woman for all purposes, because he wore women’s clothes and sometimes used the name “Michelle”. The context in which all of this took place, the endemic and institutional homophobia in England in the 70s, are all lost in this unilateral repurposing of a pivotal case to service a modern agenda. The entire page has been unsexed, with references to homosexuality incrementally erased to pave the way for alternative interpretations of Maxwell’s “gender identity”. Two days ago a photo was added with the caption “The victim, presenting as female”.

At one time there would have been outrage at the homophobia and sexism of categorising the murder of a gay man as violence against women. Now, that is the preferred interpretation of the groupthink which holds sway at Wikipedia. As one editor makes clear on the article’s talk page: “Her name is Michelle, as we know is the name she identified with. She deserves the name of the page fitting her identity.”

Changes like this are happening across the board, constantly, and have been for years. An important event in English legal history having its page renamed is not some trivial matter. The reality of the life of a young gay man surviving as a cross-dressing prostitute in 1970s London is being stolen and wholesale rewritten in service of advancing the political aims of a tiny, unaccountable and anonymous clique, without the vast majority of the world even knowing it has happened, let alone grasp the wider impact of such changes on our future information systems.

It remains to be seen if this new attempt to rename the page will be successful but what is especially notable this time is the justification for the renewed attempt:

the policy situation has appreciably changed to the point where we should re-examine this; the consensus in the most recent GENDERID RfC is that MOS:GENDERID applies equally to the names of people — living or dead — as it does to other gendered terms.

Wikipedia’s manual of style determines how such matters should be interpreted across all articles, and it is bringing all historic articles in alignment with modern, US-centric and activist-led ideas about gender, deadnaming, misgendering and identity. One editor - the same who added the “presenting as female” picture to the article and removed a reference to homosexuality - voted in support of the move, stating: “the facts have not changed from the 1970s, but the style guides have.”

This is key: taking control of political issues by enforcing specific perspectives at the policy level has global ramifications for every single article in Wikipedia. Rewrites that might once have been fought on a case-by-case basis become a lost cause at the outset, because the enforcement of specific perspectives by the style guide means that all battles have to begin there first and foremost - and the more deeply rooted these perspectives are, the harder they are to weed out. Past objections to revisions can be made redundant by changing the guidance, and as such the latest changes that favour modern sources over contemporary ones and the “last known self-chosen name” of a deceased individual eliminate the original grounds to resist these changes.

Theoretically anyone can edit Wikipedia, but if someone were to seek to challenge this they would likely run into problems since articles which touch on gender are routinely flagged as Contentious Topics, giving administrators broad latitude to impose sanctions such as article, topic and sitewide bans, for perceived infractions. This means that anyone attempting to undo the changes to this article must overcome not only Wikipedia’s manual of style, but also the policies on misgendering and identity that make expressing dissent a linguistic tightrope walk, with the possibility that going against the current consensus could allow an administrator the excuse to sanction or ban you. All of this is a huge disincentive to participate in contentious areas in a way which goes against the majority, ensuring the preservation of existing groupthink.

The efforts of some editors to align all the collective knowledge in Wikipedia with US-centric ideas around gender identity presents the whole world with intractable problems. It is hard to know how to even begin to undo this damage when those same editors have control over the processes of checks and balances, and work to very effectively freeze out alternative perspectives. This has huge implications well beyond Wikipedia itself due to its incredibly potent position both as top search result and as primary training data for AI.

To reiterate this point: allowing a tiny set of ideologues to determine the way Wikipedia deals with gender issues affects the way every search engine and every AI language model does too.

The shaping of the editorial process on Wikipedia to align with gender identitarianism has been a seemingly unstoppable process for many years. However, it has at least happened in the open, with a (mostly) public audit trail. By contrast, when the BBC’s style guide was updated to prioritise gender identity and define homosexuality as same-gender attraction, this was a unilateral and opaque decision with ramifications far beyond a single document, and has shaped all BBC output in the years since.

In the same vein, just last week, Associated Press released updates to their stylebook such that their output is encouraged to take specific, ideological positions on matters such as the appropriateness of medical interventions on minors, to the point of declaring puberty blockers an entirely reversible intervention. About a year ago, as part of its lobbying efforts, ILGA released “Guidelines For Journalists” which stated that “all medical care trans children may receive is reversible”. It is absolutely clear that a key activist goal is control over the language used by the media at the policy level. From IPSO’s recent consultation on the reporting of transgender issues to the Equal Treatment Bench Book used by judges in England and Wales, style guides and policy handbooks are obvious strategic targets for any activist group seeking maximum impact.

By convincing a comparatively few stakeholders to adopt “inclusive” language or prioritising gender identity over sex, it is possible to deny even the semblance of balance in coverage because all output has to be filtered through the approved language of the style guides and content policies. Whenever that happens, anyone that has a different perspective faces an uphill battle simply trying to get a fair hearing, article by article, report by report, while the approved linguistic and political framing propagates effortlessly as the default point of view.

None of these changes is truly independent either, meaning there is no corrective force from diversity of opinion. If courts use preferred pronouns, and journalists are told to defer to the courts, and Wikipedia defers to reliable journalistic sources, then male crimes become female ones, invisibly, and attempts to record that fact are excluded from every single part of the public record, automatically.

Content policies and style guides and now “ethical guardrails” for AI represent single points of failure both for our future information systems and our historic digital store of knowledge.

I originally started thinking of this as a sort of “meta war”, with an ongoing battle for control of political legitimacy being waged by enforcing particular viewpoints at the level above the information itself. In reality however it has been more of a meta walkover. The uniformity of thought and lack of challenge on these issues is striking, and the more that cave, the greater the pressure there is on others to follow suit.

In 1972 it would have been impossible to look at the tragic story of Maxwell Confait and forsee how he would one day be exploited as part of a vast ideological conflict being waged almost invisibly across all of our digital information systems, with far-reaching implications for our collective consciousness. Now, unless the over-arching content policies are challenged, it seems inevitable that every single historical event that can be appropriated in this way, will be.

Updated June 28th 2023

The second move attempt was ultimately unsuccessful, and the article remains in place for now. Voting closed on June 22nd with 5 opposed, 1 weakly opposed, 1 neutral and 3 supporting, so it was close and could easily have gone the other way.

It is again notable that those arguing in favour of the move cited the newly changed MOS:GENDERID policy, and those against arguably didn’t account for this very recent change. As one commenter pointed out:

MOS:GENDERID has been recently updated. With respect […], I think the new guidance fairly explicitly rejects the "use what sources at the time used" approach

So even though the numbers just carried it this time, technically they probably shouldn’t have. It remains to be seen how the MOS:GENDERID changes impact other historic articles in future.