Putting on your Game Face

In thrall to our increasingly sophisticated virtual selves

It is hardly controversial to state that readers become emotionally invested in novels and poetry, that viewers are moved to tears by films and television, and our joys and heartbreaks can be reflected back to us by songs. But at the same time, people who don’t play video games tend to look down on them as unserious toys, a vapid activity for children or emotionally stunted adults who need to grow up.

One of the most powerful and affecting experiences I’ve ever with any media, of any sort, I had while playing a video game called Rime, which released in 2017. I cannot describe the impact without spoiling it completely, so if Rime is a game you ever plan to play, please, do yourself a huge favour, and stop reading here. It is short, and not difficult, and it is best to go in absolutely blind. The rest of this piece will ruin the experience for you, so you have been warned.

Superficially, Rime is a puzzle game, with a beautiful visual style influenced by Spanish artists like Joaquín Sorolla. In it, you take on the role of a boy, with a tattered piece of red cloth for a cape, who has been shipwrecked in a mysterious land and is searching for his father. That is how it presents itself at first.

Each of the game’s levels - and there are only five - is marked with a tonal shift, with different mechanics that come into play and force you to learn new approaches and solve new kinds of problems. However, while it seems at first to be a light and simplistic platforming and puzzle game, as it unfolds Rime reveals itself to be an absolute masterclass in design and storytelling.

What only becomes apparent towards the end is that the entire game is an allegory, and each of the five levels represents a stage of grief. The mechanics of each level each in some way a reflection of that stage. The first level, Denial, filled with distractions and pointless achievements, and puzzles that divert you time and again from your true path. The second, Anger, where you are beset at every turn by a giant winged beast who dives on you every time you dare step into the light, and puzzle you solve as you progress fills the sky with more and more turbulent stormclouds. The third, Bargaining, where puzzles require the cooperation of gigantic walking machines, and all the while the architecture of the world seems to shift and confuse and confound progress. The fourth, Depression, where the world turns black and rain-slick, and none of the techniques and mechanics you have learned along the way seem to work, everything seems futile, walking is slow and difficult, and shadows close in and constantly sap the life out of your character.

It is only when you reach the last level, Acceptance, that so much of what has come before really slots into place. You suddenly find yourself no longer the boy, but the father, whose journey through bereavement the entire game up to this point represented. As your character sits in desolation in his child’s empty bedroom, holding on to that small tattered piece of red cloth, you are forced to press a single button to perform the final act that the game demands of you: let go.

I wept when I finished this, and seven years later I still think about it.

Games are a uniquely powerful form of immersive fiction, specifically because they demand active participation. For players willing to invest themselves in the experience, the emotional impact of being directly involved in storytelling like this cannot be underestimated.

While emotionally affecting, the characters in Rime are practically ciphers in and of themselves, placeholders onto which a narrative can be projected. In Rime, the emotional narrative itself is the point, rather than the characters, which helps make the impact universal and personal.

Other games are more cinematic in their experience, with a central character that the player can roleplay, from Aloy to Geralt to Nathan Drake. Here the experience is mediated somewhat by that more sharply-defined character, and while the game itself may be exciting, the player is under no illusion that they are that character. Still, players see aspects of themselves - or how they idealise themselves - in the way they experience these games, in a more directly personal way than fans who idolise characters and actors in Hollywood movies. While we may see an attractive, charismatic star on screen and wish we could be part of their celebrity orbit, that we could be like them, that we could be them, games offer a much more direct relationship. Games place control in the player’s hands, allowing the player to move and manipulate this character, posing them, taking pictures, sharing exciting moments with them over and over.

But the most complex and immersive experiences are those where the actual character in the game is intended to be a representation of ourselves, a customisable avatar, sculpted to suit our own desires. As technology and connectivity have advanced, so too more open-ended and collaborative storytelling has become possible. Where players make themselves anew in the game, and live through whatever experiences the game has to offer as their own stories and adventures. The line between in-world character and our real self outside it blurs and shifts as the possibilities enabled by more computing power advances.

How we relate to these digital avatars varies wildly from situation to situation and from person to person. Is it an extension of myself in the digital game world, an entirely different role I enjoy play-acting within that space, or a mere puppet I have no attachment to whatsoever? Am I making the avatar do my bidding as I watch the results at an emotional remove, perhaps even with disdain or contempt? Do I treat this virtual self with love, and experience its interactions viscerally and personally? Do I create multiple “selves” and treat them differently, just to experience the full variety this game world has to offer?

It reveals a complexity in what we think of as our identities, our ability to simultaneously present a multiplicity of selves, varying by context. What we do in a game world both is and is not “us”, and as the variety and fidelity offered by technological advances have increased, so too has the possibilities of tailoring that digital avatar in ways that transcend our personal limitations. Games can offer a playground to explore alternate selves, alternate possibilities of how to “be”, personalised avatars to which we can form deep attachments - and sometimes that attachment can spill out into the real world.

As people try to make sense of the various ills of the modern world - rising isolation and depression among youth in particular - much attention is rightly given to social media, to adverts, to unrealistic beauty standards, to a plague of handheld devices turning humans away from each other and seeking solace in screens and virtual lives in an epidemic of anxiety and loneliness. So many of us now live our lives embedded in markets and surrounded by media all creating a gnawing sense of inadequacy, while selling back whatever product or service might finally unlock your full potential, to live your best life, to be your best self.

Right now, there is no more seductive and immersive virtual embodiment than gaming.

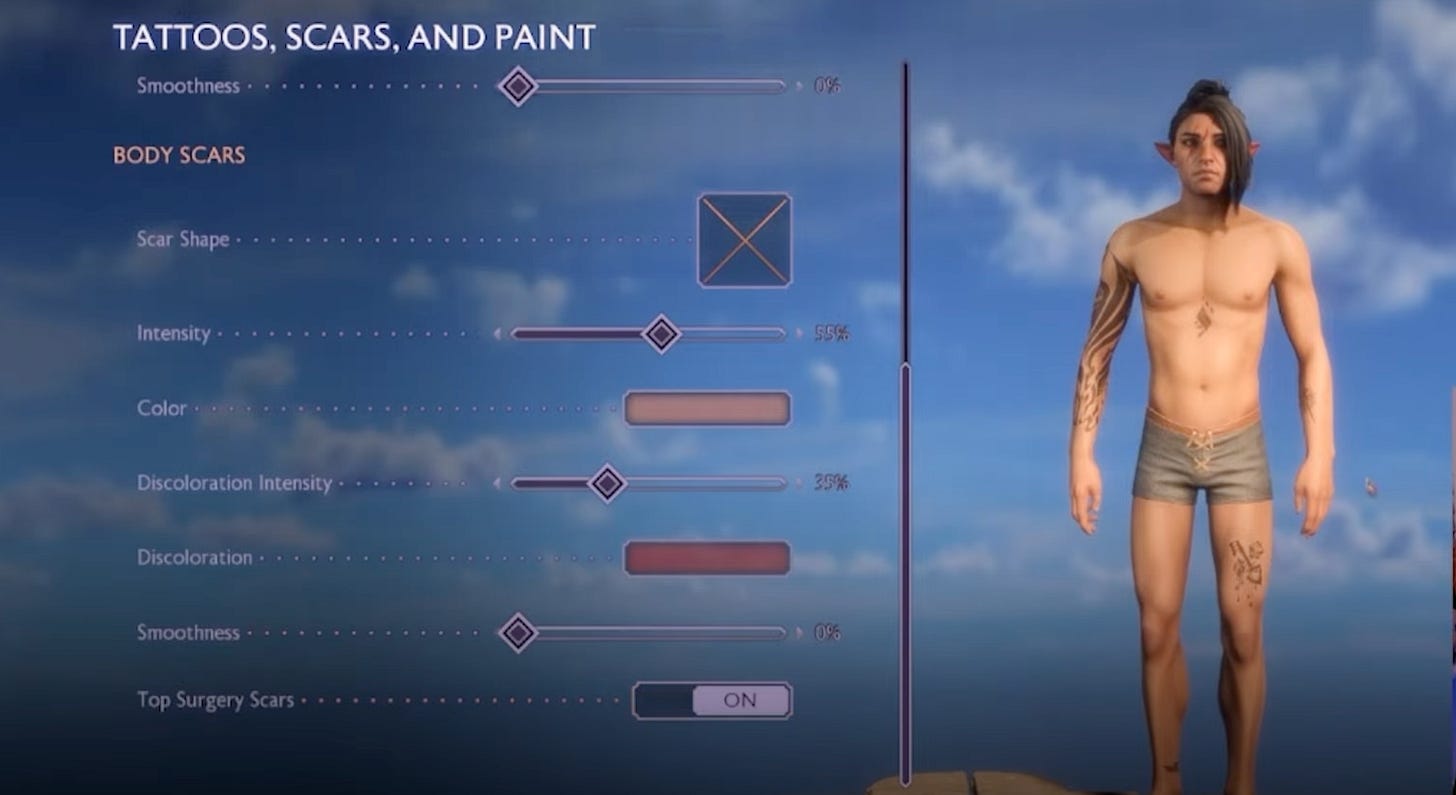

Dragon Age: The Veilguard is one such recent game which finds itself at the centre of controversy for its shoehorning of contemporary sex and gender issues in the US onto a fantasy world where such things feel out of place. As with most similar games, the game’s character creator offers a huge amount of customisation and tailoring of the in-game avatar.

Body size and shape, hairstyle, scars and tattoos, the possibilities are mind—boggling, and you can sculpt your in-game avatar to your heart’s desire.

However, one notable addition in this latest iteration of the Dragon Age series is a specific option to enable “top surgery” scars.

How we think about this says a lot about how “culture” works, how ideas are normalised and propagated, until they become an unquestioned part of society. “Top surgery” itself is a cutesy euphemism for “radical surgery to remove healthy breast tissue to superficially masculinise female bodies”, and that is without getting into the contested and controversial area of why it is being done in the first place. This would not have been acceptable in any way just a few short years ago.

A toggle for “self-harm scars” would not be acceptable, would it? But if not, why not, and for how long? Maybe today we would recognise that glorification of self-harm will lead to further self-harm in the real world - but where would we be if some prevailing section of Western culture decided that “self-harming” is a stigmatised identity, and as such should be authentically represented in a drive for inclusivity and representation? These rapid shifts to sanitised language and public adulation of the formerly unthinkable demonstrate the malleability of social norms, and it is impossible to say with any certainty what is not acceptable now won’t be celebrated next year.

Is it wrong to find this concerning? Is saying it is grotesque merely a moral panic, the latest in the long line of overreactions to depravity and violence in video games?

These aren’t things that have arisen naturally and unobtrusively from the game world itself, but are a projection of present-day cultural obsessions onto it. For some, the possibility of creating an in-game representation as wish-fulfilment is seductive, and having options such as this have every possibility of becoming fixations that are ultimately harmful - yet the politics behind such choices prevents anyone involved in the process from pointing at or describing that harm.

There is a growing relationship between crafting idealised digital avatars in video games and attempting to fashion an idealised version of ourselves in the real world, as in this 2018 piece in Vice:

During my adolescence, I spent hours of every day in other worlds. I have had many bodies, many names, and many lifetimes. The sorceress I played on Diablo II was just lines of code on a computer […] she has since been reborn again and again in other black mirrors, on other platforms, in other games.

The boy in the mirror is gone, my mother’s stained-glass lily still resting on his chest. And I have become someone much more like that sorceress that I met when I was a child. My hair looks like hers. My body, too. […] I was growing up in a male body, and, while I felt completely in charge online, I had little control over my offline life. Unable to wear what I wanted, to look how I wanted, to be seen by others as I saw myself, I felt detached from myself

The line between fantasy and impossible reality is not merely being blurred here. Rather, such fantasies are treated as proof of their own reality, where playful ideas have become fixations, and the impossible becomes a constant insatiable quest for perfection of an idealised self.

These days the game itself is no longer the game, but merely part of a larger experience, a vast interconnected community. When a specific way of viewing the world is embedded in games and all the connected and supporting platforms all at once - in Twitch’s terms of service, in bans by Reddit admins and Discord mods for stepping out of line, in sanctions on Tiktok or Instagram or Youtube - it becomes a powerful closed system for circulating and enforcing specific ideas about how and who to be. Rather than seeing any cause for concern, modern obsessions around sex and gender are treated universally in this ecosystem as a righteous crusade for liberation and autonomy, and questioning whether stories like the above have any other legitimate interpretation has become unacceptable and unsayable.

We live in an increasingly alienated world, fuelled by a dominant capitalist ethos that fixates on crafting some idealised version of the self as the pinnacle of human liberty. At every turn dangling the possibility of some perfect level of self-realisation, self-actualisation, freedom and liberation, transcending your meagre existence, where the only thing holding you back is your own drive and will to assert dominion, take control of your own life.

In that context, the escapism offered by gaming has moved far beyond some trivial pastime, and is now a multi-billion dollar global industry that makes more money than movies and music combined. Moreover, this industry is in a unique position to influence culture, not only because of the youth of the primary demographics of players, but also the strength of attachment it is possible to feel with in-game avatars. This is especially true for those most vulnerable players, the awkward and isolated, the anxious, the autistic, the depressed and lonely, for whom games offer a lifeline to a form of connection that can seem impossible in the real world.

Humans are malleable, social animals, adaptable, storytellers and story-believers, and we have the ability to swiftly reshape our behaviour - or have that behaviour reshaped - through shifting cultural norms. Games have the power to tell us stories in a way that can immerse us and affect us more deeply than any other media. In ideological hands they can do great harm as a vehicle for spreading and normalising a narrow view of the world as the “true” way. But in the hands of artists, like the creators of Rime, they can open us up to new perspectives and hold a mirror up to the human condition in ways limited only by our imagination.

Lovely insightful piece

This post would have been better without the long aside on Rime, which adds nothing of substance to your argument.