Political Noise

How recommendation systems drive algorithmic claustrophobia

There is little doubt these days that social media has had a hugely toxic effect on political discourse. Cancel culture, dehumanisation and bullying, purity spirals and echo chambers: some of our most tribal behaviour has been supercharged and now plays out on an unprecedented scale. What is less clear is how much of this is driven by human dynamics playing out over a new communication medium, and how much is down to the ubiquitous algorithmic feed of recommendations and suggestions employed by the social media giants.

At their most simple, machine learning recommenders are optimising for some specific goal. The classic and most easily understandable example is monetisation, ie how to get people to spend as much as possible.

For example it is common to target the conversion rate - what percentage of users turn from non-spender to spender - and treat increasing this figure as one primary goal for system optimisation. The approach then is to run experiments, using everything from changes to user interface, to the variety of recommendations presented, to user-specific high-value deals, to the timing and rate at which these are presented to the user, all of which will produce different rates of conversion. When an experiment produces a higher conversion rate, then that is deemed a success and becomes the default, and further experiments are run against that, in a relentless, automated drive to optimise the target metric: converting non-spenders into spenders.

So far, so obvious. Of course different people may respond to different things in different ways and these sorts of optimisations are not one-size fits all. Users are typically segmented and targeted for different experiments and different optimisations - those in one country might respond differently to those in another, men differently to women, over-60s differently to under-30s.

But it is worth stressing that the whole point of this is to produce behavioural change.

This is not a benign approach dedicated to providing the healthiest experience for anyone who happens to use a service, but an aggressively optimised pipeline for creating the behaviour the service demands from the maximum possible number of people. If this comes at a cost of coercion, trickery, and a slow drip of unconscious manipulation in order to extract maximum value, then that is just the logic of the marketplace in action. Businesses that are effective at producing behavioural change will survive and those that do not will die.

Feed-based systems like Twitter and TikTok don’t have to rely on crude demographic data for segmenting their userbase - they build up a sophisticated picture of who you are based on what you have interacted with. And the principal source of revenue is advertising which means that by far the most important metric is attention. The probability of clicking, of sharing, of watching a video beyond a certain number of seconds, how much content you engage with - the more active users a platform has, the more valuable it is to advertisers, and the more engaged users are the more adverts they will see and possibly click on.

So we have created the most effective systems ever for manipulating human behaviour in order to capture as much attention as possible, in ways that are invisible and unknowable to individuals subject to it. Unfortunately, while we largely seem to accept this is on some level pretty bad for society, much of the discourse around the effect of these systems is about pushing individuals to the “left” or the “right”, which represents a gross oversimplification of what is actually happening.

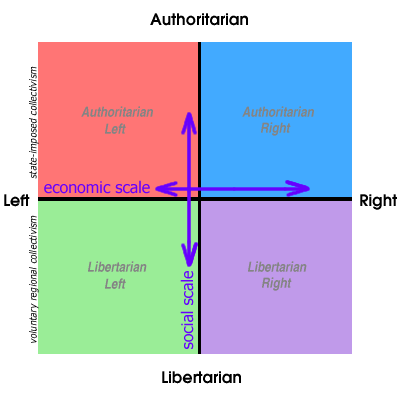

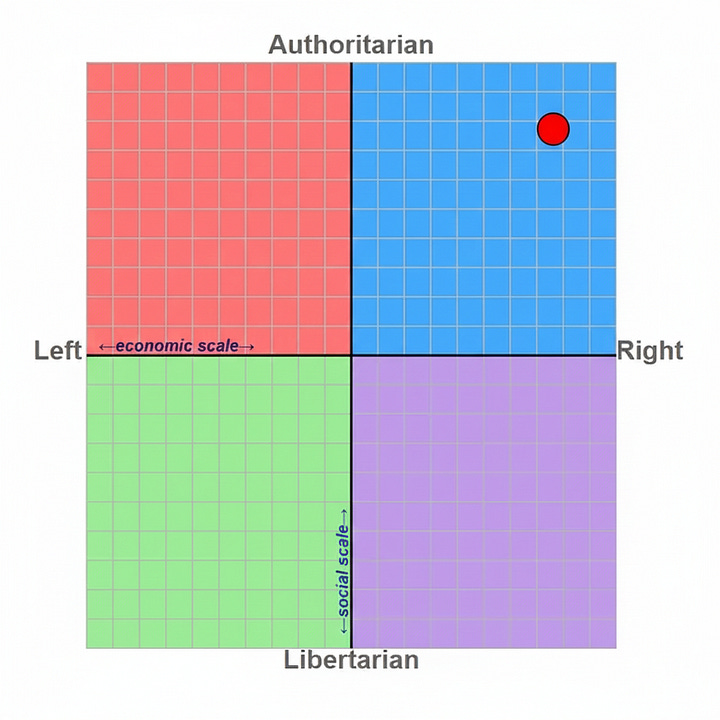

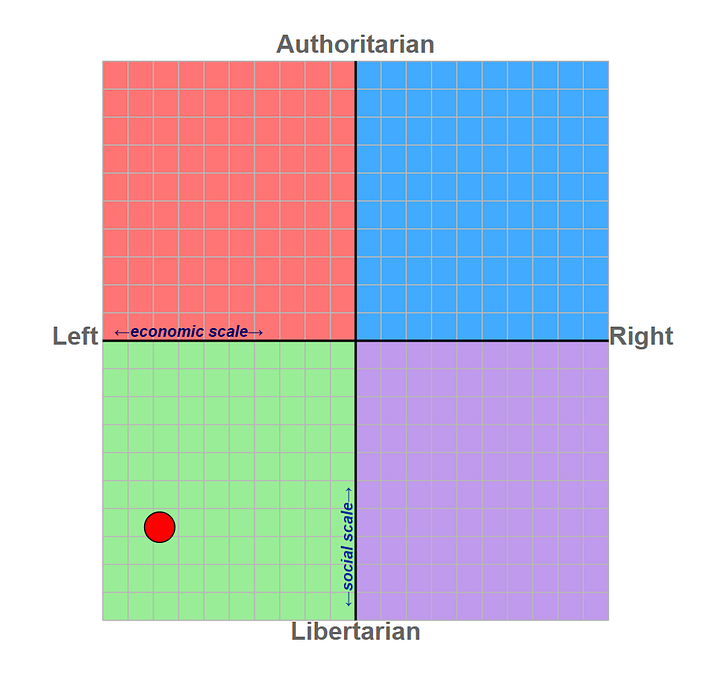

Notions of left and right are far too broad to capture the breadth of our individual political positions. One attempt to improve on this is the political compass, which expands the left/right spectrum with an additional libertarian/authoritarian axis:

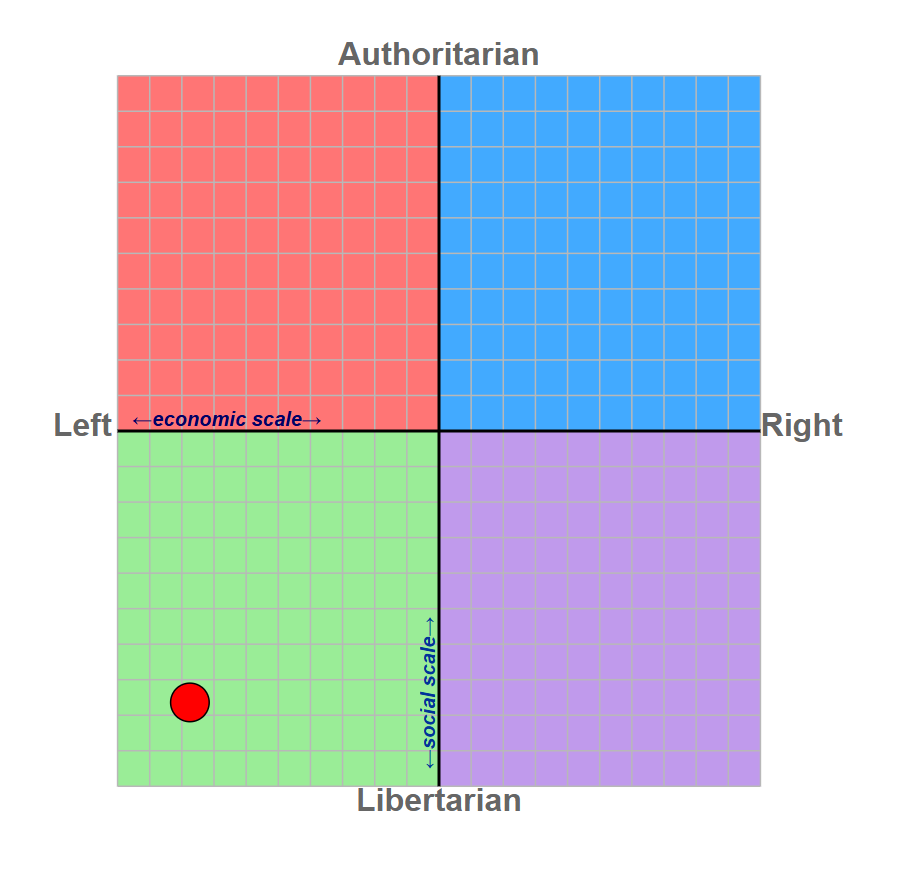

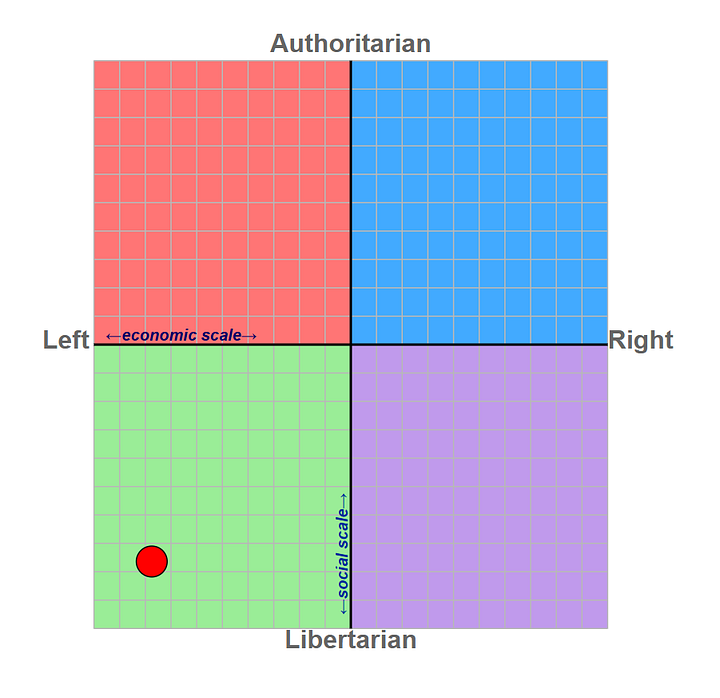

So, rather than a simple left/right opposition, more complex political leanings can potentially be conveyed. For example, a left/libertarian would appear here on the political compass:

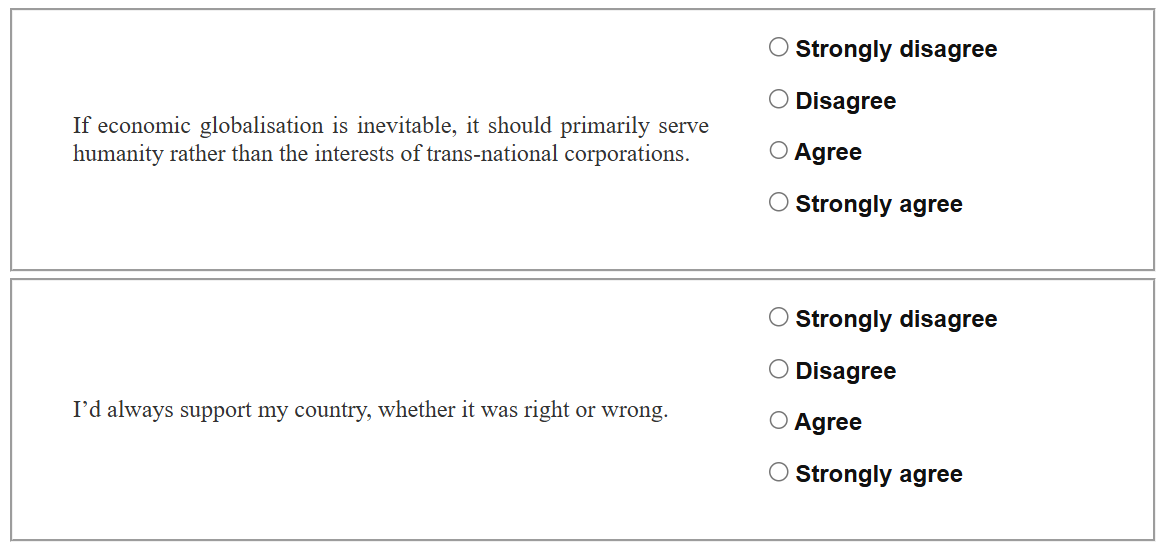

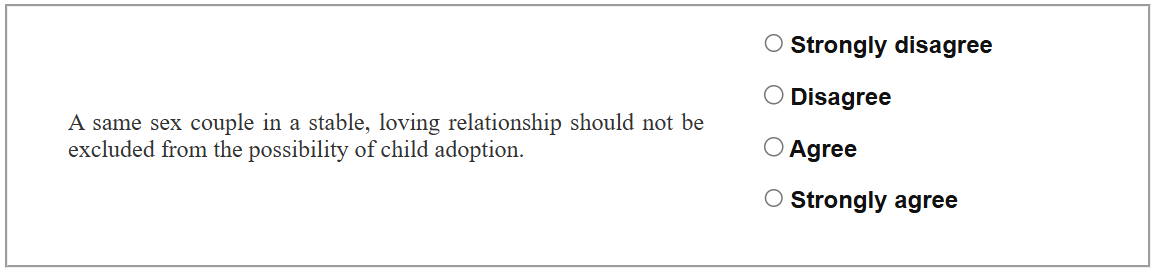

But even that is a crude simplification, because what the political compass is doing is taking a questionnaire with 62 multiple-choice questions and baking down the answers into some sort of average position on a two-dimensional grid. These are questions such as the following:

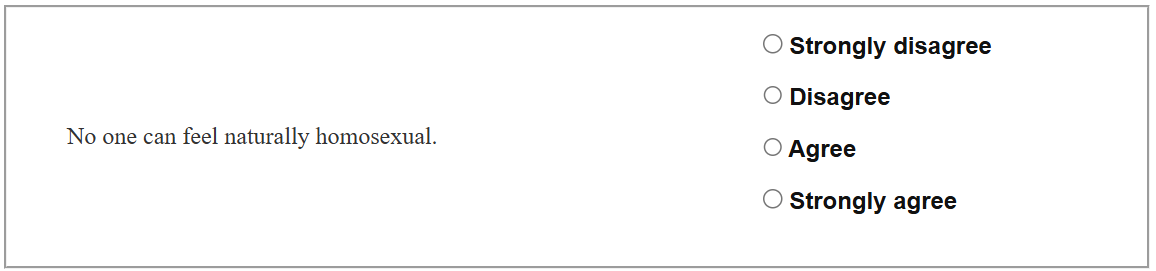

A single value on the political compass doesn’t really convey the range of opinions actually held by an individual, it is a simplification. A useful one, to be sure - but another way of thinking about it is that the individual is represented by all their answers to those questions. If each question has an answer 0-3 (from strongly disagree to strongly agree) then another way of representing that person’s political compass position is:

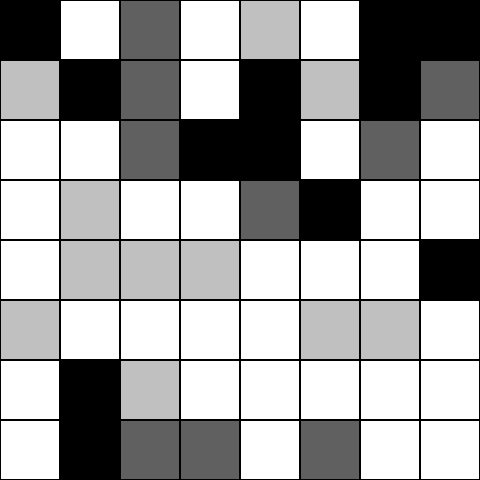

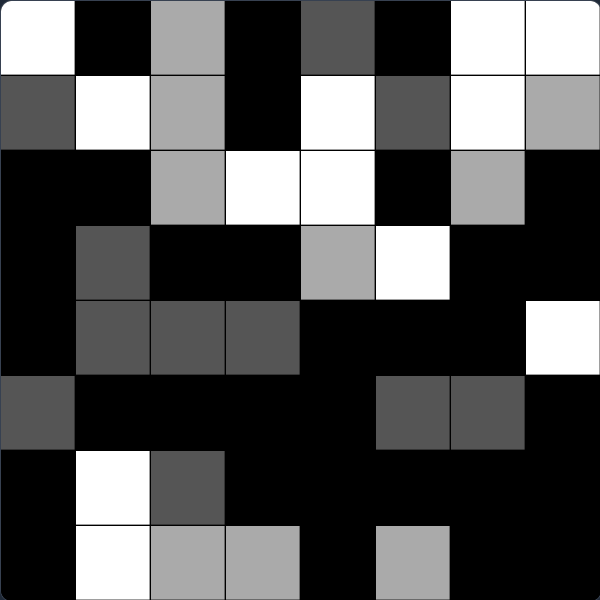

3,0,2,0,0,1,2,3,0,0, (etc…) That string of numbers is meaningless at first glance to a human, and would be hard to interpret even if you had a list of questions to hand. But perhaps another way of visualising these answers is in something akin to a chessboard, where the colour of each square denotes the answer:

black = strongly disagree

dark grey = disagree

light grey = agree

white = strongly agree

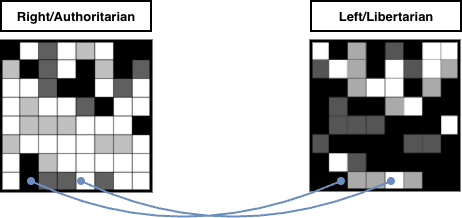

In this model, the grid below represents the answers to the political compass that would result in a right/authoritarian viewpoint:

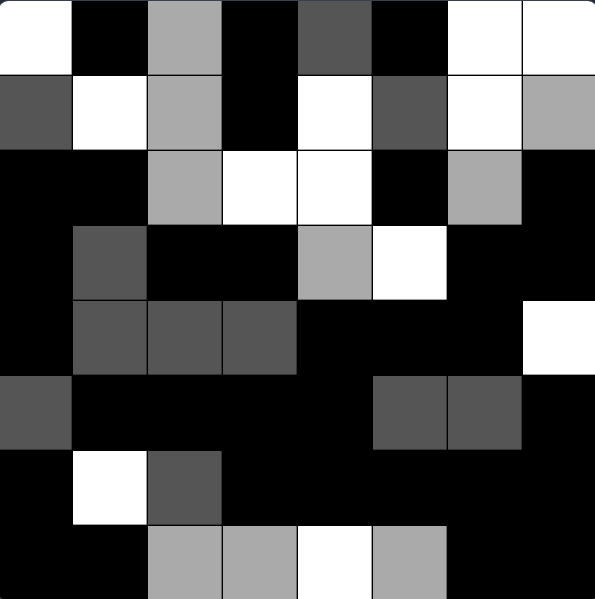

And here is how it would look for a left/libertarian position:

We can tell with a glance at the political compass image that these two are polar opposites politically. It is slightly less obvious by looking at the grid representation of the answers, though when viewed side by side it is possible to see that these are negative images of each other.

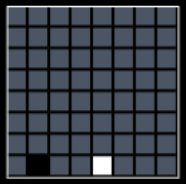

Now consider the following slightly different set of answers. This is a position that is still largely the same as the above left/libertarian grid, but with only two different answers, resulting in a position that is slightly more authoritarian:

The only difference is the answers to the following two questions:

These two people have virtually identical left/libertarian politics according to the political compass, with only two points of disagreement. This underlying distinction is invisible to anyone seeing the political compass result, and even that is only marginally different in the first place. Most people would consider these two to have broadly the same politics.

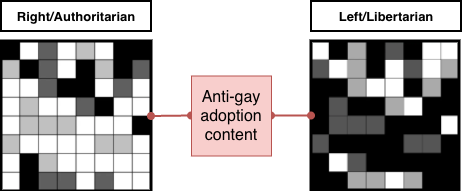

However, these are the two questions, which represent a radically different point of view on matters relating to sexual orientation:

Someone could have answered these questions differently for a wide variety of reasons. Perhaps they think all sexuality is a spectrum and any monosexual desire is inherently limiting, resulting only from cultural mores. Or perhaps they think homosexuality is inherently unnatural. Or they oppose all adoption in principle.

The meaning underlying these choices range from the mistaken to the regressive to the utopian. We cannot truly understand a person’s viewpoint just from this question. Nor can we understand it from a glance at a chessboard abstraction of their answers to multiple political questions, nor an aggregate score on the political compass, nor from binary labels like “left” and “right”. Everything is a simplification, a compression of complicated data into ever smaller and less meaningful abstractions.

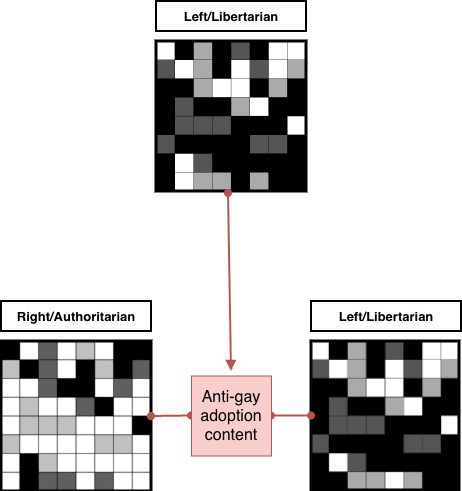

Returning to the use of machine learning to drive behavioural change, let’s say for the sake of argument that the below grid represents 64 datapoints a social media platform holds about its users. These - purely to simplify this example - match the questions in the political compass, so in the figure below the two black and white squares correlate to - the difference between the original two left/libertarian individuals (ie, the questions on sexual orientation).

Now imagine a platform is using machine learning to optimise the engagement rate of its users. It wants to turn casual users into obsessives who will click and engage and produce more content, and this platform is unconstrained by what the actual content being engaged with is, the impact this has on the mental health of these individuals, or on society as a whole - it is just blindly optimising for attention by relentlessly exposing users to content to see what works. Through experiments finds that users with strong signals in these two squares (ideally, fully black or white) are highly engaged.

The platform does not know the meaning of these squares. It does not know that it may correlate with homophobia or utopian idealism. It hasn’t even outright asked a question in the way the political compass does - it simply responds to the behavioural data it has accumulated and tries to optimise each user’s feed for maximal engagement.

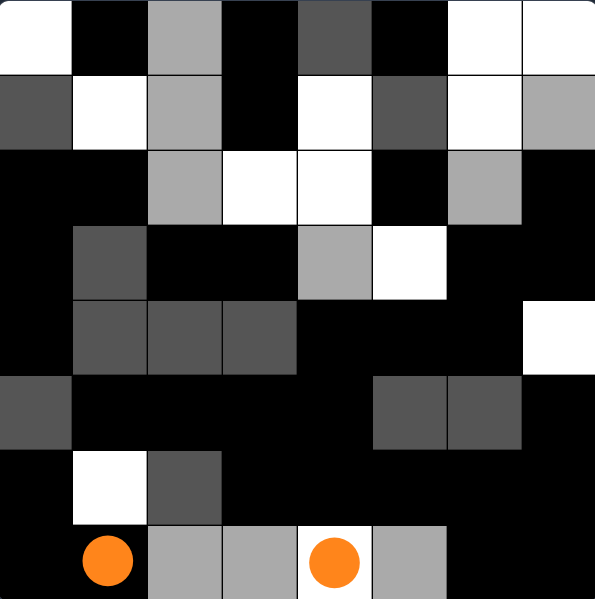

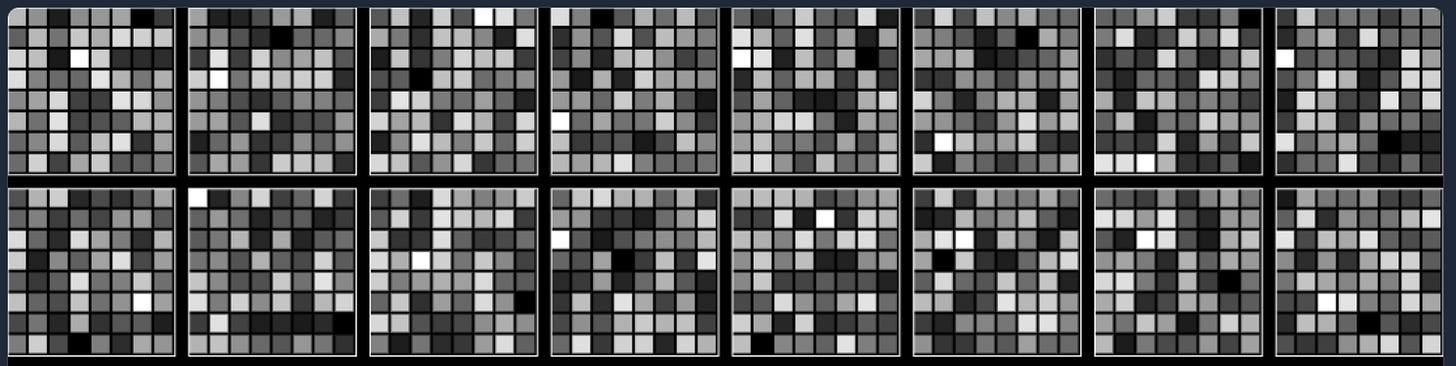

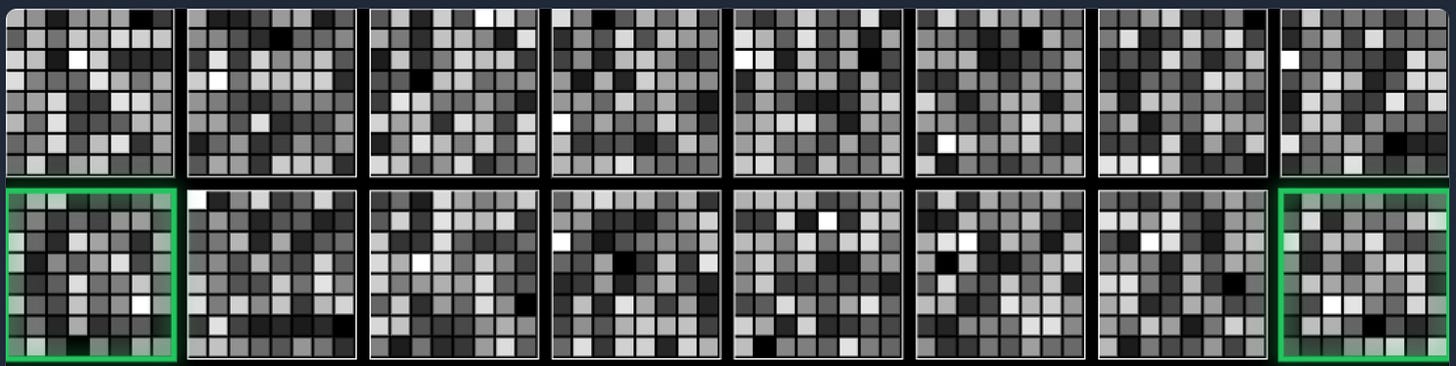

Now consider the following is an illustration of the noisy datapoints this platform holds about 16 random users. Rather than straightforward black and white, each point is a shade of grey, indicating some level of certainty about this behavioural data:

It just looks like static really. We, as humans looking a this visualisation, can’t tell what they have in common, if anything. And this is to be expected - humans are complex, and we understand that our own individual preferences are unique. Based on the above, could you guess which two are the most similar overall?

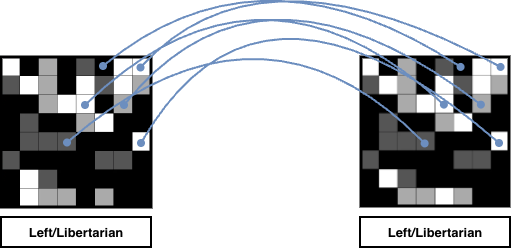

It is these two:

Again, it is trivial for computers to perform a comparison such as this near-instantaneously. To the human eye, the grids look like noise, but to the machine, the proximity of two users in this multi-dimensional space is a roadmap for social contagion. If one of those two individuals clicks on a specific inflammatory headline the machine has a high probability that another, similar user will as well. The more information that can be gathered, the stronger the signal amidst these datapoints, the more reliable these predictions will be, and the more effective those predictions will be at increasing engagement.

If we can gather more info, the uncertainty of those views collapses into much clearer positions. By removing the shades of grey over time, collecting more data and producing stronger signals - and thus stronger opinions - much more black and white pictures emerge. For example, in the below example, we can see how gathering more signal eventually finds this one specific matching pattern of behaviour:

But if this pattern is a desirable one that equates to greater engagement, then the logical next step is not simply to detect it, but to create it. How can those initially yellow squares be “nudged” such that anyone that could exhibit this behaviour, does so? If there is a way of doing so, a combination of content and presentation and timing that will unconsciously lead individuals to publicly express views they had not previously considered, then machine learning recommendations will find it.

There is a tradeoff between exploiting what the system already knows about us and exploring possibilities that might gather more data or push us in a new direction. But the relentless, optimising logic of attention as a metric of success fuels the drive to obtain ever more data, to detect stronger signals, to produce more refined suggestions, to generate more attention and more data. And in reality these illustrative squares are a massive simplification of the thousands of dimensions of datapoints gathered about our behaviour on social networks.

It is the collection of ever more data in order to extract signal from noise that is fuelling radicalisation on social media. As these systems try to improve their certainty about our behaviour by gathering more and more of our interactions, so do we too become ever more certain and forthright in the opinions we express through the constant repetition of those actions and the constant feedback of social approval or approbation. Machine learning recommendations provide each of us with an individually tailored on-ramp to whatever extreme views we might one day be capable of holding. These systems have no specific end goal in mind, as long as we keep clicking. We might start with reasonable questions and - through the slow dripfeed of ever more strongly held opinions - find ourselves ten years down the line cheering behaviour that we would once have found abhorrent.

All while flattering ourselves that such radicalisation - such conversion - only happens to other, stupider people.

With advertising as the dominant revenue model for online content, it was inevitable that machine learning recommendations designed to maximise revenue would find ways to devour ever more of our attention. Surfacing points of bland agreement does not produce maximal engagement, so systems drift toward divisive, emotionally triggering material. It is the ruthless logic of the market, and it cannot self-correct, even as it eats away at the fabric of society.

Returning to our original left/libertarian examples with opposing views on gay adoption, they might find in reality that this difference of opinion simply never arises. In their personal lives it might not be discussed - or if it was it could simply be something they agree to disagree on. Whatever the case, they have far more in common than that separates them.

Meanwhile two individuals with radically opposite politics might never find they had a shared viewpoint about gay adoption. Or, even if they did, they might find it is in reality only superficially similar, and held for very different reasons:

Whatever the case, machine learning systems do not see the crude left/right compression of these views, or even the two dimensional left/libertarian vs right/authoritarian labelling - or even the simple grid of political compass answers I’m using in these examples. What they see is a vast, many-dimensional array of datapoints covering content the user has previously interacted with, which can be used to predict what they may interact with in future. Datapoints such as these will inevitably drive social media recommendation engines to surface more content likely to gather interactions from these users. These systems do not care whether this is promoting content that is (in this example) anti-gay adoption, only that they have a high probability of attracting further attention, and feedback, and data, to drive more attention, and feedback, and data.

To each user, interacting with such content is designed to be seductively easy, and consequence free. Social media platforms want to keep you engaged, they want you to act unconsciously, scrolling, clicking, liking - and with the illusion that these are disposable and consequence free actions, as easy as breathing. But with the shift to these opinions being expressed publicly online on a continuous basis, the act of liking or retweeting content becomes - to the outside observer - part of an indelible personal manifesto. Thoughtless statements or casual clicks transformed into strongly held political convictions, date stamped and archived and screenshotted and searchable and permanent.

Having publicly interacted with content that another left/libertarian may find unpalatable, this then works to create a rift between these users. But - crucially - showing this interaction to another left/libertarian will drive further interaction. Again, the systems do not care whether this comes in the form of public shaming, condemnation or outright hostility - they only care that it generates further interaction, and further data.

Social media can rapidly create the illusion of being part of a like-minded “tribe” and then just as rapidly shatter that illusion, by laying bare the faultlines between individuals. Faultlines that, on a one-to-one basis, we are capable of navigating, but are utterly unequipped to deal with when scaled up to the hundreds or thousands and acted out on a public stage with millions able to see and judge our actions.

Once you see someone who you imagine to be part of the same “tribe” expressing wildly different opinions about something important to you, it creates a feeling of dislocation and unease - and social media is on hand to provide the analgesic for that pain. Soothe your discontent by scrolling and agreeing with those who are equally horrified. Or don’t, and find yourself self-censoring for fear of being isolated by the “tribe”.

By surfacing our most divisive opinions to the people most likely to be offended by them, these systems force us into a state of constant anxiety, always at risk of conflict. As the saying goes, “the map is not the territory” - but here, the map (in the form of the behavioural data) is in constant feedback with the territory (our selves). The map and territory shape each other until they become indistinguishable. We eventually become a caricature of ourselves, repeatedly performing the actions that gain us public approval, all while terrified that one wrong datapoint could be surfaced to the very people least equipped to forgive us for it.

We are left living in a state of algorithmic claustrophobia, trapped in a feedback loop where our most divisive, unformed impulses are taken to be the entirety of our selves in public. Only that which can be quantified remains. Our private internal thoughts, all our nuance, disappear as we internalise the logic of the surveillance systems, performing for attention in public only those aspects of us that can be captured and collated as data, until every other part atrophies.

Once you become immersed in these systems, at some point, the greatest fear isn't being watched - it is the fear of no longer being tracked at all. Of not being broadcast and amplified. Of facing non-existence, anonymity and oblivion.