New England Journal of Misinformation

Yet another partisan attack on the Cass Review

In January 2025, the New England Journal of Medicine published an article titled “The Future of Gender-Affirming Care — A Law and Policy Perspective on the Cass Review”. The article is little more than a blatant attack on the integrity of the Cass Review, and sets out the following main points:

The Cass Review sets an unattainable bar for evidence and violates international standards

It was secretive and biased

Its methodology was flawed

While throwing in a few other potshots for good measure, and ending in some absolute gibberish about gender policing.

While only a “perspective” piece, that it was published in the form it is reflects quite badly on the editorial standards of NEJM. That is, the piece isn’t simply bad or contentious, but factually wrong in such a fundamental way that it renders the whole article incoherent.

The term “review” is used interchangeably to mean multiple different things throughout this article, so some basic terminology first:

Systematic review: a form of academic study that assesses the current state of literature in a field by searching for all published literature on a given subject and assessing the results according to a preregistered criteria, with the aim of producing the best overview of the available evidence.

Peer review: evaluation of an academic work by experts, a necessary precondition for academic publishing.

The Cass Review: a four year independent process chaired by Hilary Cass, which examined the NHS care for gender-questioning children and young people and delivered its findings in a final report. As part of that process, the Cass Review commissioned multiple peer-reviewed systematic reviews, which were conducted by the University of York.

Throughout the original piece, the authors shift confusingly between attacking the overall process of the Cass Review itself, the final report of the review, and the peer-reviewed systematic reviews it commissioned. Hopefully the distinctions between these will be clear in what follows.

The Cass Review sets an unattainable standard of evidence

The foundational claim of the NEJM article is the following:

The Review calls for evidentiary standards for GAC [gender-affirming care] that are not applied elsewhere in pediatric medicine. Embracing RCTs [randomized-controlled trials] as the standard, it finds only 2 of 51 puberty-blocker and 1 of 53 hormone studies to be high-quality.

Unfortunately, this is all completely false.

In this instance, they are referencing the York systematic reviews which assessed the evidence base on puberty blockers and hormones:

The puberty blockers review assessed 50 studies, of which one was high quality - and this was a cross-sectional study, not an RCT.

The hormones review assessed 53 studies, of which one was high quality - and this was a cohort study, not an RCT.

Both reviews also considered moderate quality studies (25 and 33 respectively).

In this short quote, the authors get the total number of studies wrong, the number of high quality studies wrong, the standard of evidence wrong, and the requirement for randomized-controlled trials wrong.

This is quite a lot of wrong in a short passage, but without this claim, much of the rest of the article falls apart. The authors insist half a dozen times throughout the article that the Cass Review is holding gender medicine to a “higher standard” than other fields, which is based on this completely false premise - the reviews used an entirely attainable standard (as evidenced by more than half of the papers assessed meeting that moderate/high standard), and there was no requirement for RCTs. This is the sort of very basic fact checking you should expect a piece would be subjected to before being published by NEJM - this isn’t a matter of opinion, it is outright misrepresentation of peer-reviewed research.

This claim of an overly high standard is the basis of other allegations against the Review in the article. For example, the authors claim the Cass Review somehow violates pharmaceutical procurement policy by demanding unattainably high standards:

More generally, the Review’s circumscribed approach to drug approvals is out of step with pharmaceutical law and policy in both the United Kingdom and the United States. […] Former Chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s plans for MHRA to implement the “quickest, simplest regulatory approval in the world for companies seeking rapid market access” conflicts with the evidentiary standards the Cass Review endorses for GAC. Similarly, U.S. law often does not require randomized trials showing a clinical benefit of drugs before approval

But since the Cass Review didn’t specify onerous requirements or demand RCTs, this whole argument is irrelevant.

Still, having falsely decided that the peer-reviewed systematic reviews applied an unattainable standard, the authors go on to speculate this was because the final report of the review was not itself a peer-reviewed scientific publication:

The report’s application of a heightened evidentiary standard probably stems in part from its deviation from standard medical scientific process. Specifically, it lacked peer review

Once more, the authors have shifted target, applying their (wrong) criticism of the York systematic reviews to the final report of the Cass Review. But since their criticism of the peer-reviewed research was incorrect in the first place, none of this follows, and claims of deviation from “standard medical scientific process” is just empty hyperbole.

The authors then claim that - since the final report was not a peer-reviewed publication, it would violate US federal law:

The U.S. Information Quality Act requires peer review for government-published scientific information that “will have or does have a clear and substantial impact on important public policies or private sector decisions.”3 Yet the Cass Review and its principal conclusions that made international headlines were not verified by experts. The Review thus departed from standard practice; indeed, as mentioned above, if the U.S. government issued a report in a similar manner, it would be violating federal law.

The citation here is a federal rule about science commissioned by the US government requiring peer-review. Any federal agency producing its own research internally or communicating scientific data to the public has to be subjected to some level of peer review.

So this is a hypothetical application of a US rule for government-published science - but that’s not what the Cass Review was. It was an independent service review commissioned by NHS England, not a government publication - and the science it commissioned is all peer-reviewed, and published in the British Medical Journal.

The Cass Review was more than a single document, it was a four-year process, chaired by Hilary Cass, and its final report is not “scientific information disseminated by the government”, but rather the conclusions and recommendations of that independent review to NHS England, which summarises the findings of multiple peer-reviewed papers it commissioned as part of that process.

The conclusions were indeed “verified by experts”, because these are the conclusions of the peer-reviewed systematic reviews, and this was fed back to NHS England to inform future service provision. These were then further “verified by experts” because independent medical bodies, including NHS Scotland, further assessed the review’s findings and endorsed them. The idea that you can apply the requirements of US federal bureaucracy to this sort of independent service review and then argue it would “violate federal law” is simply bizarre.

The authors make completely baseless assertions about what “standard practice” is, while conflating multiple aspects of the review, and inventing an inapplicable standard as an excuse to condemn the Cass Review as a whole.

The Cass Review is biased

On top of the fundamental errors and straw man arguments, there is also an unhealthy amount of conspiracism and mudslinging:

observers must speculate about who else participated in the manuscript’s drafting — and whether they held bias against LGBTQ+ people. […] There is evidence of antitransgender bias in invitations to oversee and participate in the report. […] Cass and her colleagues did not attempt to filter out people with antitransgender bias.2 Indeed, according to the Review, a third of health professionals whom the authors chose to interview agreed that “there is no such thing as a trans child.”2

To support this the authors cite Cal Horton’s critique of the interim report (which I previously discussed here), but the ultimate source of this claim is the clinical engagement process undertaken as part of the review. I have to wonder if the authors of this piece even checked Horton’s claims, or simply took the description there at face value, and further selectively presented it here as (shock, horror) evidence of bias in the Review.

The Cass Review conducted multiple sessions of stakeholder engagement over the course of its four years. As well as a clinical expert group of NHS Trust nominees, and a panel of 33 specialist gender clinicians, 102 primary and secondary care workers outside of gender services were involved in multiple panel sessions.

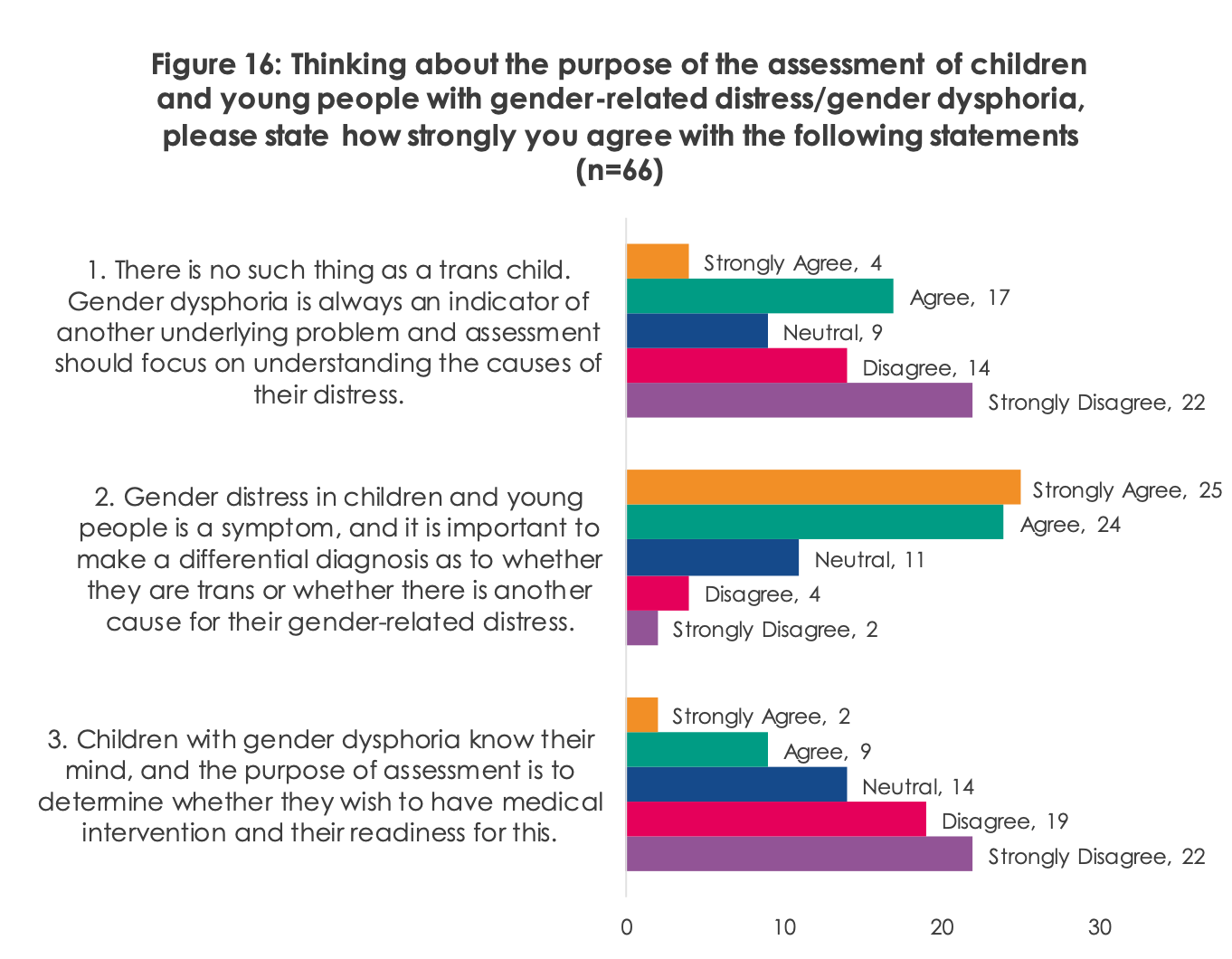

Of these, the fourth independent activity involved 66 participants, and the following survey was conducted:

These questions represent different positions on a spectrum of interpretation of “gender distress” and are described in the review document as intentionally worded to prompt discussion among participants:

It should be noted that the Review team is aware that these statements are polarising and are intentionally worded as such in order to [elicit] a clear response from participants. During the second group workshop many participants said that whilst they completed the activity, they felt that the statements did not allow for enough nuance and valued the opportunity to explore it further through discussion. As Figure16 indicates, professionals in our sample held a broad mix of views about the purpose of assessment. However, we see most consensus when it comes to the second statement: gender distress in CYP is a symptom, and it is important to make a differential diagnosis as to whether they are trans or whether there is another cause for their gender-related distress. When prompted on this during the second group workshop, it became clear that for many participants this statement relates to professionals wanting to shift the conversation away from an ideological position and highlights the importance of taking an exploratory approach. During this discussion, participants clarified that from their perspective, this was not about denying the feelings of the CYP, but rather about providing relief from issues that often exist alongside gender nonconformity. For them, the purpose of an assessment framework is to explore what course of action may help resolve or reduce distress in the longer term.

From this we see that the overwhelming view of clinicians is that gender distress is a symptom, and that it is important to identify and address underlying causes. From a clinical perspective, starting from the point of view that a child who presents with gender distress is, in some fundamental way, a “trans child” forecloses alternative explanations. There are obvious clinical disagreements as to how to interpret and diagnose a child presenting with “gender distress”, but broad agreement on an open-minded and exploratory approach.

The NEJM authors however are of the opinion that holding any view other than theirs is “anti-transgender bias”. What they seek is to exclude other clinical perspectives they disagree with - to “filter out” what they see as bias - based on a single-minded belief that their own position is the only correct one, and they criticise the Cass Review for not doing so. But the whole point of sessions like this is to gauge the true scope of clinical disagreement. Deciding up front what answer you want to get is not science, and this is why it is so important that independent reviews such as this are indeed conducted independently, and not by those with a vested interest in a particular outcome.

And, one more nitpick - this is not “a third of health professionals whom the authors chose to interview”, but rather as this was the outcome of one activity, involving only a subset of professionals interviewed, it is actually 15% of the total.

The Cass Review was methodologically flawed

Despite only being a short perspective piece, the authors pepper the article with a Gish Gallop through some claims from critics of the review, none of which stands up:

Commentators also point out that the Review (and associated studies) misrepresented the data behind its conclusions,1 had both a high risk of bias according to the Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Systematic Reviews (ROBIS) and a “substandard level of scientific rigor,”1 and improperly excluded non-English articles, “gray literature” (non–peer-reviewed articles and documents), and other articles not identified by its simplistic search strategy.1

Shifting target yet again, the criticism they are referring to in this passage is all directed at the nine peer-reviewed publications by York University commissioned by Cass, rather than the final report. These claims are all derived from a Yale white paper/amicus brief, which itself depends on a preprint paper, both of which I have previously written about. I won’t repeat myself at length here, but suffice to say none of the points made in the above paragraph should be taken at face value. Aside from anything else, rather than being “simplistic”, the York reviews performed the most comprehensive literature search of any systematic review in this area.

But I will point out the hypocrisy that, having complained throughout this article that the Cass Review’s final report wasn’t “peer-reviewed”, what this paragraph actually does is repeat weak, false and misleading arguments from a non-peer-reviewed white paper, which itself cites a non-peer-reviewed preprint paper, to criticise the actually peer-reviewed literature commissioned by the Cass Review.

The effect of citing these claims here is to get weak arguments from sources which are not peer-reviewed and not published in any reputable journal, platformed without serious scrutiny by the NEJM.

Bonus sexism

Having made a poor case against the Cass Review, the authors several times emphasise that they must be on the right side of history by waving vaguely at gender equality and claiming that disagreement must be propping up “gender norms”. This makes little sense, and as presented here really does highlight how gender studies theorising has become a hollow cargo cult of feminism, with the recitation of thought-terminating cliches and shallow buzzwords taking the place of serious insight and analysis. For example:

Moreover, similar calls for higher standards are not applied to cisgender young people receiving gender-affirming care. Cisgender girls sometimes seek hormone therapy for hirsutism;

That the authors interpret girls receiving hormone therapy for hirsutism as “gender-affirming” is highly revealing. It is a concession that girls should be hair-free, as that is indicative of a feminine gender, and thus by removing hair hormonally, this act becomes gender-affirming.

This demonstrates how deeply sexist this worldview and obsession with gender affirmation is, viewing every act through the narrow prism of aspirations towards masculinity or femininity.

Medicine has long been deployed by people seeking to enforce gender norms.

Yes it has, and one such example would be referring to medical treatment for female hirsutism as “gender-affirming”.

Then there is this:

The Review’s departure from the evidentiary and procedural standards of medical law, policy, and practice can be understood best in the context of the history of leveraging medicine to police gender norms. Recent efforts to increase the presence of women in medicine, improve access to reproductive services, and offer GAC seek to break from that history, but the Cass Review represents a return to the past.

Just so we are absolutely clear, this is a perspective piece by two men, criticising a four-year independent review led by a woman, which commissioned a whole series of peer-reviewed systematic reviews, all also written by women, as somehow a setback in “efforts to increase the presence of women in medicine”.

The authors end on a manipulative mashup of the abortion and intersex gambit, both so beloved of those with no real arguments left. Agree with our position, or you must be anti-abortion:

Mainstream medical views have shifted on both abortion access and care of intersex people. But the Cass Review suggests that some actors continue to focus on policing gender in the context of transgender rights. Indeed, U.S. GAC bans exempt intersex surgeries — which suggests that such laws are designed not to protect children, but to enforce the gender binary. The Cass Review’s unacceptable departures from medical law and policy are best understood in a similar way.

Bans on abortion are bad, therefore… the Cass Review must be? The Cass Review commissioning systematic reviews which found an appallingly weak evidence base for medical interventions on children is… enforcing the gender binary, and that’s the same as patriarchal control over female reproduction? It. Does. Not. Make. Sense.

Conclusion

The opening paragraph of this article in NEJM reveals what I believe to be the real concerns of the authors, and what lies at the root of all of the attacks on the Cass Review emanating from the US:

in the United States, the Cass Review has been used to defend new state bans on GAC for young people — including one in Tennessee that currently sits before the U.S. Supreme Court.

The US is so deeply politically divided, even more so now, and whether or not it is ethical and evidence-based to medically intervene in the normal development on vulnerable, mostly gay children is not being decided through the scientific method, but playing out in the courts. A partisan, political divide where how you interpret the evidence decides which political team you must be batting for - and, conversely, which side you support determines what the evidence must be. That the authors manage to tie their position to abortion cements how deeply interconnected these issues are in US political terms, despite having nothing whatsoever in common.

Within these polarised court battles and political posturing, there really is no room to manoeuvre, and no space to concede that the Cass Review may have a point. The Review’s cautious approach to the evidence for paediatric transition offer a stark rebuttal to those arguing in court that this is a robust, safe and evidence-based practice. Unable to produce better evidence, advocates have been left with no alternative than to attempt to undermine the Cass Review. It has to be condemned and discredited, and so we get contributions such as this, published complete with obvious, foundational errors in the NEJM.

There is nothing wrong with the authors having a strong opinion on what they call “gender-affirmative care”. There is nothing wrong with the NEJM publishing that opinion, as part of the cut and thrust of academic disagreement. But that is not what this is - it is a shabby attack on the Cass Review, a recitation of activist talking points in service of a wider political agenda, and one in which the NEJM is an all-too-willing participant. The Cass Review has to be destroyed, for The Greater Good.

Excellent, thorough, and VERY patient.

At the same time, the aim to shift discussion from “does gender medicine harm or help” to “is the Cass Review good or bad” is clearly intended to get everyone to stop looking at the first question, which remains the important one.

So even if it were possible to prove Dr. Cass to be a mad hobo in the pay of Big Intersex Abortion, gender medicine is still either harmful or helpful. The evidence is piling up so fast that it is super harmful that advocates of it would really rather we discussed “Cass, hobo or no?” instead.

The approach of the believers in "gender-affirming care" to the Cass Review is very reminiscent of the “debunking” of the 2023 Cochrane Review's findings regarding the effectiveness of masks to slow respiratory virus infections, and it shouldn’t surprise anyone who has followed NEJM’s publication record on mask mandates during the pandemic. Ideology > science all the way, on both topics.