Beef Trifle

A new review in the British Journal of Sports Medicine insists men are weaker than women, really.

A new systematic review on the comparative performance of transgender athletes has recently been published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine which has arrived at the surprising conclusion that the literature “does not support theories of inherent athletic advantages for transgender women over cisgender”.

The paper, led by authors from São Paulo University, covers several different metrics and comparators - upper body strength, lower body, cardiovascular fitness, transwomen compared to men, transmen compared to men, and so on, and crucially across key metrics the authors claim no difference between female performance and male after hormone therapy. In the paper, the authors go so far as to state:

the absence of strength disparities between transgender women and cisgender women found in the current review was consistent and contradicts narratives framing male puberty as conferring irreversible athletic advantages despite GAHT [gender-affirming hormone therapy]

The paper itself does not exist in a political vacuum, and multiple times references bans and policy issues, stating that the findings of this review endorse

nuanced, sport-specific policies rather than blanket bans

This is (predictably) making all the headlines you might expect for its conclusion that there’s no difference in athletic performance between men on cross-sex hormones and women:

Trans Women in Sport Have No Advantage Over Cis Women, Study Finds

Physical fitness of transgender women ‘comparable’ to that of other women

New Study Once Again Shows Trans Women Have No Physical Advantage Over Cis Athletes

Review Of 52 Studies Finds No Fitness Advantage For Trans Women Over Cis Women

And so on…

To illustrate the problems with this paper, its conclusions, and the way these are being represented in popular media, I will simply address the single most implausible supposed finding: that there is no difference in upper body strength between female athletes and males after cross-sex hormones and testosterone reduction.

This is the sort of claim that doesn’t even pass the smell test. Upper body strength is one of the largest differentiators between male and female athletic performance - the difference in punching force for example is so vast that there is virtually no overlap.

On even a cursory inspection of the paper it turns out this whole thing is a mixture of linguistic sleight-of-hand and the mixing of quite different studies into a meaningless result.

This is long and detailed and covers multiple issues but the tl;dr version is: these findings are almost entirely down to one paper by another group of researchers at São Paulo University which compared weak men to national-level female athletes.

Grip Strength

The authors used grip strength as a proxy for upper-body strength. Previous reviews of the difference between male and female grip strength have found huge differences overall:

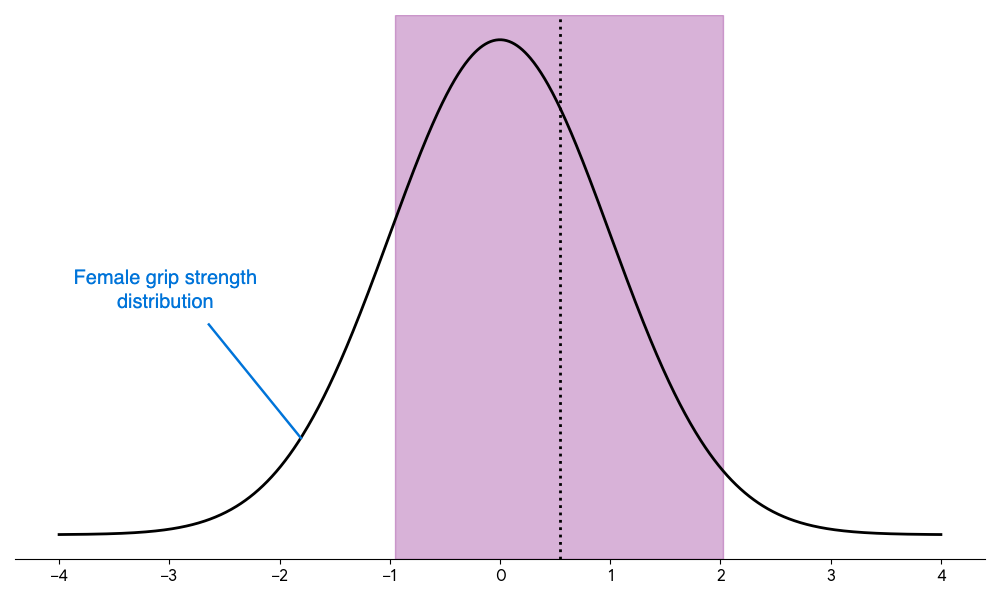

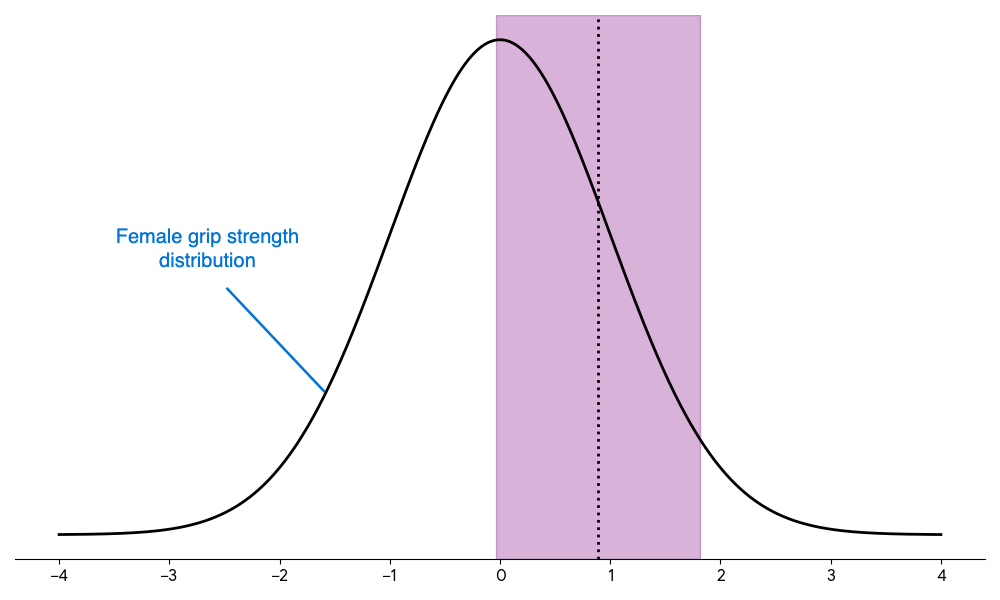

90% of females produced less force than 95% of males

Almost all men have a stronger grip than almost all women, and this is a finding that correlates linearly with lean muscle mass and hand size - ie, that men are on average larger and have more muscle mass tends to confer a greater grip strength.

In this new review, the authors looked at four papers that measured grip strength in different cohorts of female participants compared to males on different regimens of cross-sex hormones and/or testosterone suppression, over different periods of time, with different levels of physical activity. The result when considering all four papers to produce a combined estimate of the difference in grip strength was:

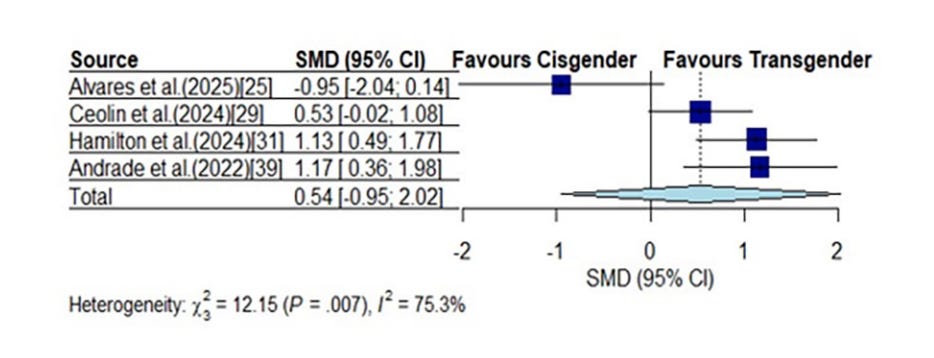

No significant differences in upper-body strength were observed between transgender women and cisgender women (SMD 0.54, 95% CI −0.95 to 2.02, I² = 75.3%, substantial; GRADE: very low) (figure 2A). These results remained consistent across all categories in the sensitivity analysis (online supplemental table S8a).

Let’s explain what these numbers mean.

SMD = Standardized Mean Difference. This is the pooled average of the advantage trans-identifying male participants had over female ones, in terms of standard deviations. What this means is that the average finding of these four studies is that, despite hormone therapy, male participants were still 0.54 standard deviations stronger than female ones (or, stronger than about 71% of females, on average).

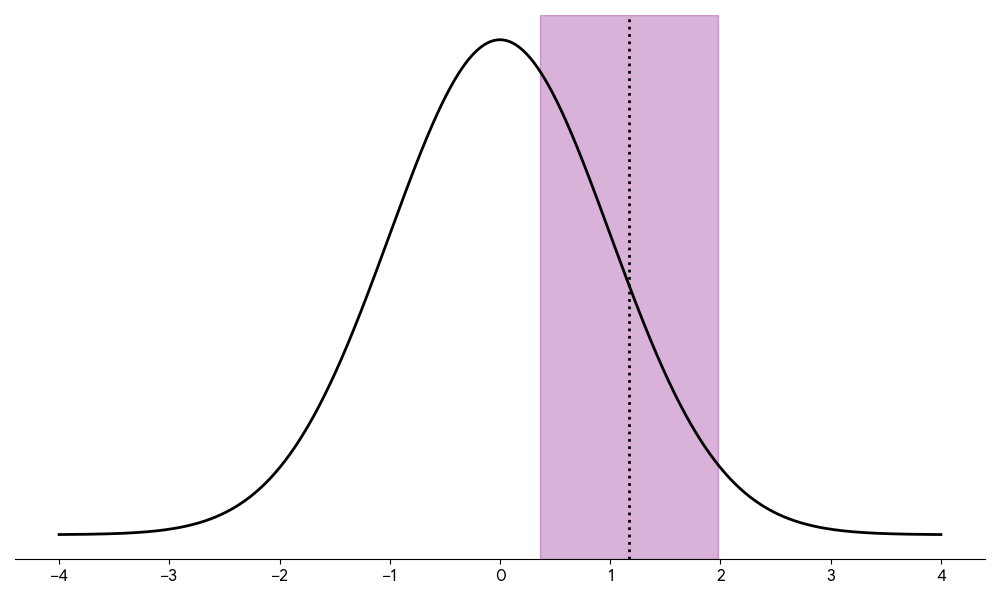

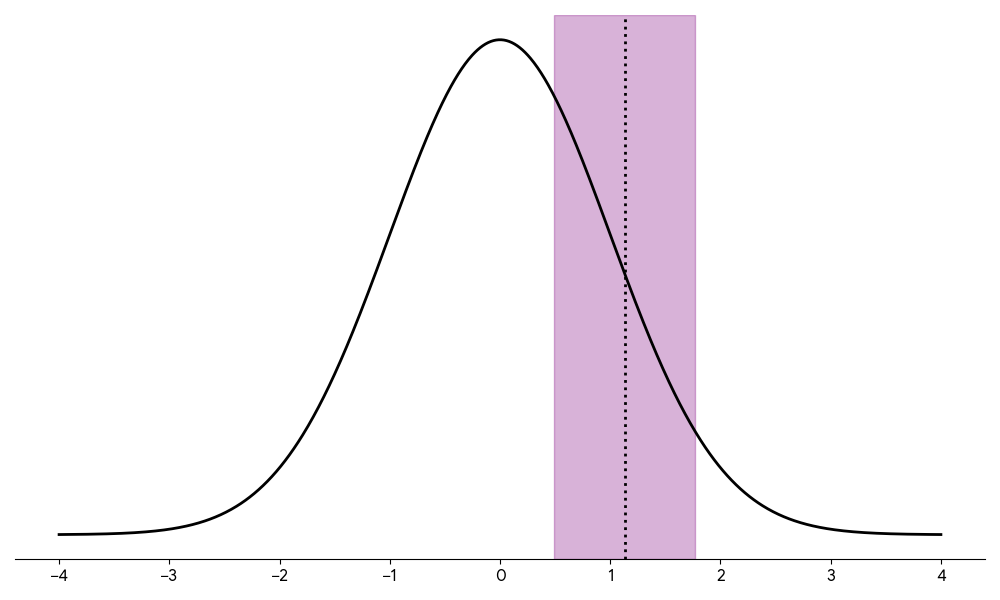

CI = Confidence Interval. This is the range of values that we are 95% sure the “true” average lies in. Using the authors’ frequentist statistical framework, if a CI crosses 0 it isn’t statistically significant and thus the null hypothesis (ie that there is no effect) cannot be rejected. In this case, this value is so wide as to render the result pretty well meaningless. So from looking at these four papers we can be 95% sure that the average trans-identifying male is between 0.95 standard deviations weaker than, to 2.02 standard deviations stronger than, the average woman. Or, in other words, the average male after hormone therapy is anywhere from weaker than 83% of women to stronger than 92% of them. For a male, this is a range somewhere between geriatric frailty and peak athleticism, and is therefore meaningless.

I² = Between-study Heterogeneity. This is a measure of how similar the studies are to each other, and gives a percentage change that any variance between the studies is down to real differences rather than chance. A value of over 75% is classed as substantial heterogeneity, ie there is a high chance that the wide variance is because of differences between the four studies.

In short, they found a moderate upper-body strength advantage, but it was not statistically significant, probably due to a large variance as a result of very different study methodologies, and the overall conclusion was very low certainty.

Basically, they found nothing, or nothing that could be said with any confidence anyway.

Instead of just saying they found nothing, however, they say there is no statistically significant difference. This is one of those classic misleading abuses of scientific phraseology, like creationists dismissing Evolution as “only a theory”.

There is a vast gulf between “we found a moderate difference, but it is not a robust finding statistically and so we can’t really say it is a real difference with any confidence, or whether the real value is drastically higher or lower” and “there is no difference”.

To reiterate, here is the phrasing the authors adopt in their conclusions:

the absence of strength disparities between transgender women and cisgender women found in the current review was consistent and contradicts narratives framing male puberty as conferring irreversible athletic advantages

The authors did not find an “absence of strength disparities” - what they found was that they could not be certain of the moderate-to-large strength disparity to a level of statistical significance.

Bearing in mind that the difference between male and female grip strength is between 2 and 3 standard deviations, a not-statistically-significant range of -0.95 to +2.02 means you cannot rule out that there are basically no differences between males with or without cross-sex hormone therapy and/or testosterone suppression. It would be surprising if such interventions had no effect, but it would be even more surprising if they eliminated it completely. There is a substantial difference, already well-established in the literature, and the point of a systematic review like this should be to establish how much of that well-established difference is eliminated by hormonal interventions.

The authors find they cannot say exactly how big the difference is - but instead of saying “it looks moderate-to-large but we cannot say for certain and further research is needed”, they instead make the overbroad claim that there is an absence of strength disparities, despite the fact that - with confidence intervals you could drive a supertanker through - they also failed to reject the (far more likely and well-supported) hypothesis of a retained male advantage.

Linguistic trickery aside, things get worse when you start drilling down into the actual studies.

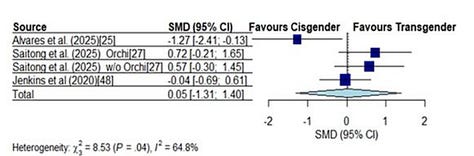

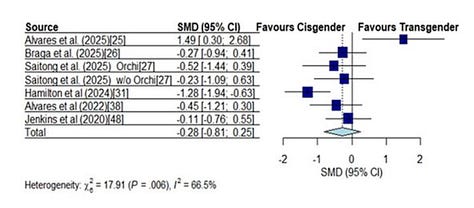

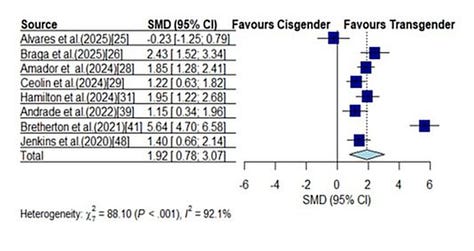

The “not statistically significant” difference is derived from a pooled estimate from four papers. Here is Figure 2A from the systematic review, showing how each paper estimated the difference in grip strength between female comparators and trans-identifying males:

A quick glance at that shows that one of these papers is substantially different to the other three. While three found that the male participants were stronger, one found that they were considerably weaker. But there are issues and confounding factors across all four papers, so it is worth looking at them all.

Alvares et al 2022

Firstly, Figure 1A actually contains a typo - the citation “Andrade et al (2022)” should be “Alvares et al (2022)”. Andrade et al is a study on transmen, and not applicable here. This is a trivial issue that will doubtless be corrected at some point.

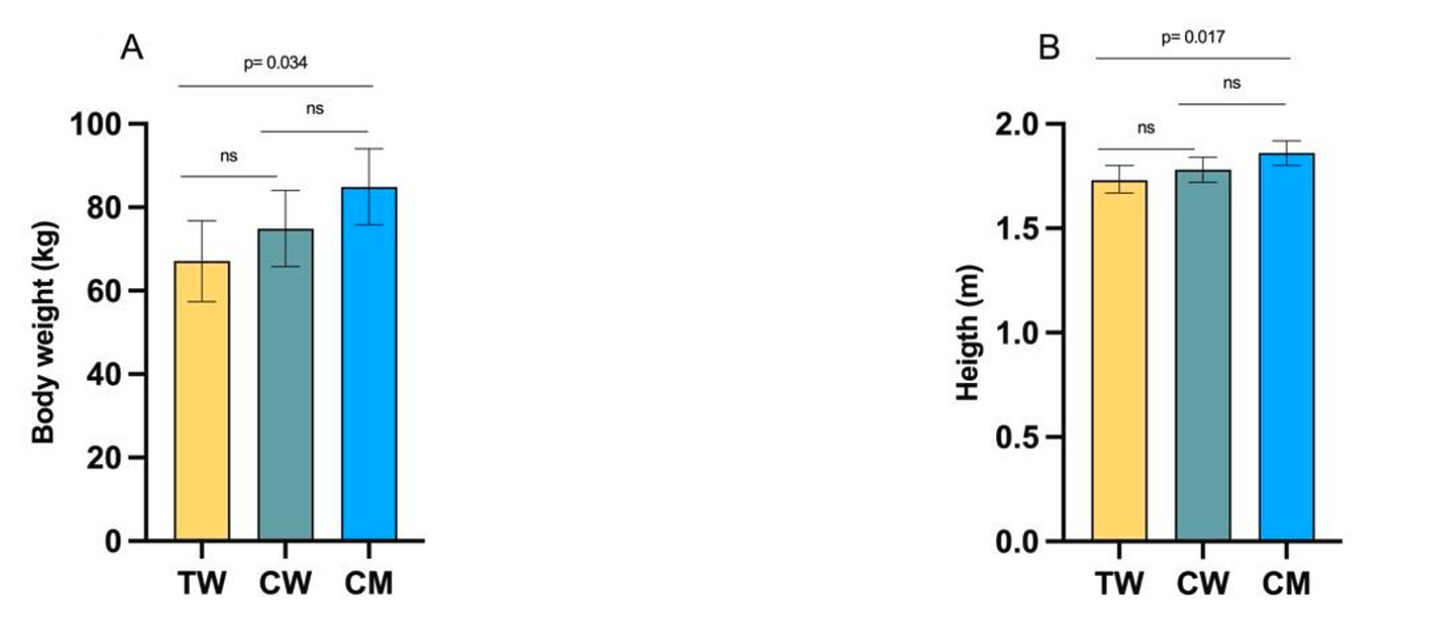

Alvares et al (2022) was a study 15 trans-identifying males on a variety of long-term hormonal interventions and 13 female comparators by a group of researchers at São Paulo University. The trans-identifying males were described as non-athletes, and they had been on a variety of cross-sex hormones and hormonal suppressants for an average of 14 years. While 13% of these were described as “very active”, this was in comparison to 54% of the female participants. The heights and weights were average in both groups (the females were 13cm shorter and 18kg lighter on average).

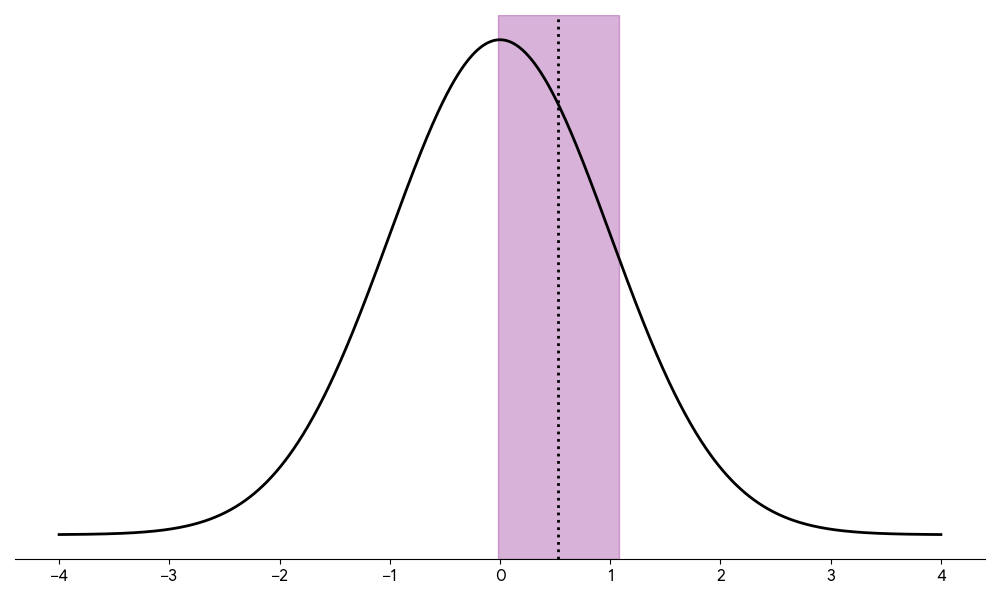

The grip strength test took the average of three attempts with the dominant hand, and found 35.3kg in the trans-identifying males vs 29.7kg in the females. This equated to a very large, statistically significant strength advantage among the trans-identifying males of 1.17 (0.36 to 1.98):

Hamilton et al (2024)

Hamilton et al (2024) was a study of 23 trans-identifying males on cross-sex hormones and 21 female comparators. Participants were physically active, and described as “competitive”, which was defined as training three times per week - however all training volume and physical activity levels were self-reported, and as the study itself notes they “may suffer from selection and recall bias”. The average duration of cross-sex hormones was 6 years, so these are again long-term effects. The height and weights of the participants was again reasonably average, with the females 20cm shorter and 13kg lighter on average.

Unlike Alvares et al (2022), the grip strength test took the average of three attempts with both hands, and found 40.7kg in the trans-identifying males vs 34.3kg in the females. This again meant a very large statistically significant difference in grip strength: 1.13 (0.49 - 1.77)

So these first two papers are measuring grip strength slightly differently and among different populations, but despite different absolute values come to a similar differential, which shows a very large male strength advantage is retained despite long-term cross-sex hormones.

Ceolin et al 2024

This is where things start to get a little interesting. The title of Ceolin et al 2024 is “Bone health and body composition in transgender adults before gender-affirming hormonal therapy: data from the COMET study”. This is a protocol for a longitudinal study in Italy where 26 trans-identifying males 26 female controls were selected from a larger cohort and given baseline bodily metrics tests prior to any hormonal interventions. By my reading, the systematic review wrongly seems to treat this as representing one year of hormonal treatment, when it seems to be the pre-hormonal baseline data. In table S4 in the systematic review’s supplemental material, this paper is described as covering cross-sex hormones, but that dose and duration was not recorded. This seems to be misleading - if this really is a baseline, pre-intervention study then the dose was not recorded because there was no dose. This would seem to violate the protocol of the systematic review by directly comparing exposure studies with a non-exposure study.

Additionally, these are non-athletes, and according to the protocol, controls were matched by age and “sex assigned at birth”, but it is ambiguous whether that means that the trans-identified males were matched with female controls or male ones.

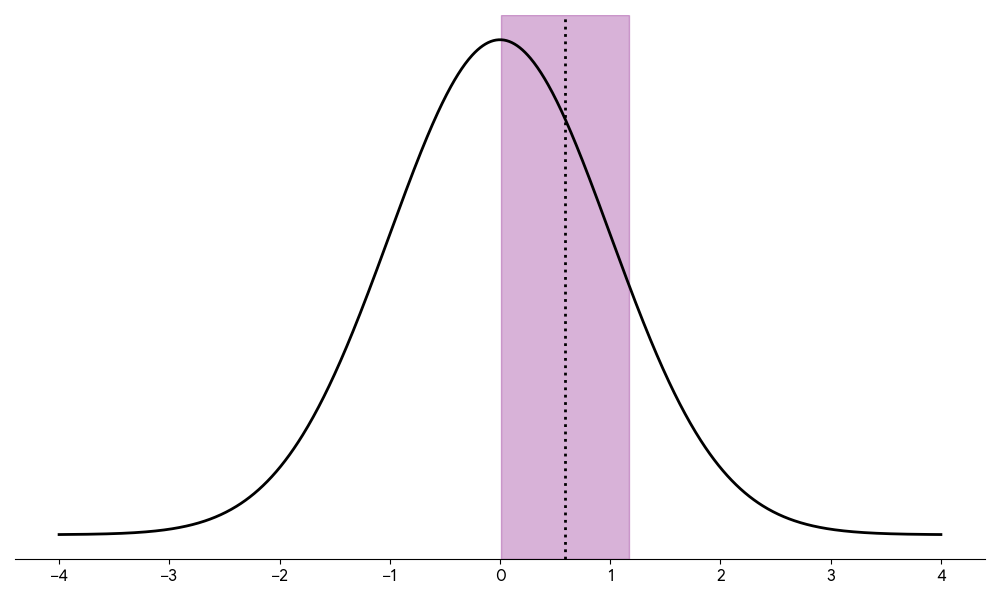

This study measured the average of the maximum grip strength of both hands, and found that the male participants recorded 35.46kg, compared to the 30.8kg of the females - a slightly narrower difference than the previous two studies.

The result is that it found that trans-identifying males without hormonal intervention had a medium advantage in handgrip strength over matched female controls, although not quite statistically significant: 0.53 (-0.02 to 1.08):

This is quite a surprising finding. It is expected that males will have higher grip strength than females, and it is plausible that this will decrease after cross-sex hormones. To find only a moderate and not statistically significant difference in two groups of 26 before cross-sex hormones is unexpected. One possible reason is a greater variance in age in the male vs female participants (most of the males seem to be in the 18-33 range, while the females are more like 20-29). The heights are not recorded, but the male participants were below average strength for males in this age group before any hormone treatment, and less than 6kg heaver than the females.

The same Italian team did a followup on this cohort after one year of hormonal intervention, and I cannot explain why this later study was not included in the systematic review.

In that study, by my reading it seems that two of the baseline cohort dropped out, so they include a recalculated baseline for the remainder, and an updated measurement after one year of hormones. The revised baseline grip strength was given as 32.21kg before hormones, and 34.91kg after one year of hormone treatment - so the trans-identifying male cohort actually got stronger after a year on hormones.

This is another surprising result, which could be explained by participants at the younger end of the scale growing up, or unrecorded changes in activity level over the previous year. There are numerous possible confounding factors - but if we calculate the difference between the trans-identifying males and female controls in this later study it seems to result in a statistically significant moderate advantage: 0.59 (0.01 to 1.17).

I admit I am no expert, but I cannot explain why Ceolin et al (2024) has been included despite not covering hormonal interventions, and the later followup has not.

Alvares et al 2025

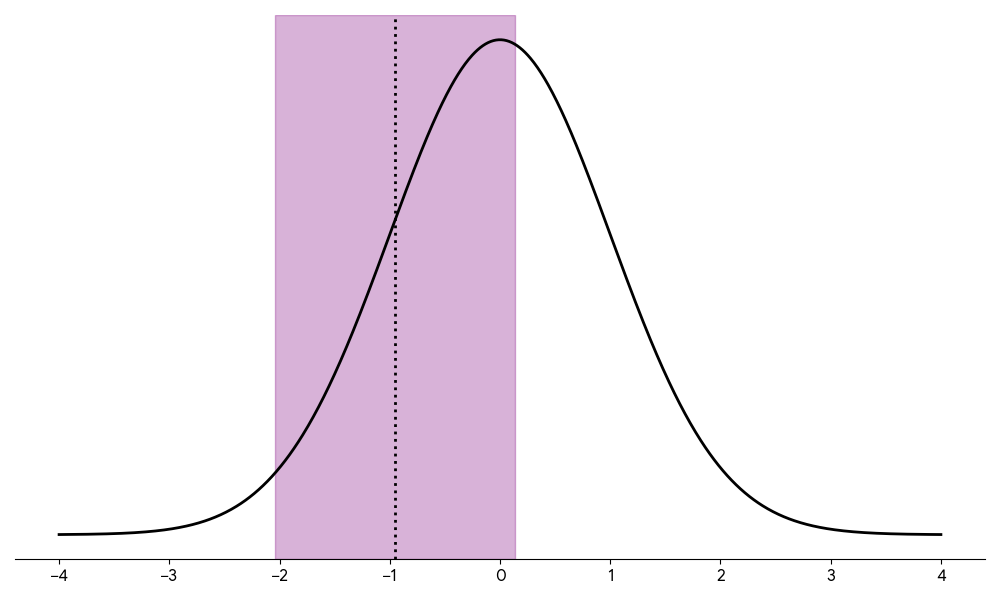

Now we come to the real outlier. Alvares et al (2025) was a study including 8 trans-identifying males on cross-sex hormones, and 7 females, all of whom were described as “amateur” volleyball players. Here the average period of hormonal intervention was not directly stated, but a minimum of 1 year was part of the inclusion criteria, and the systematic review authors have derived a value of ~7 years from the paper.

Unlike all other studies, this actually found that the trans participants were significantly weaker than the female ones, though this was again not statistically significant: -0.95 (-2.04 to 0.14)

This is an astonishing result - after cross-sex hormones men become massively weaker than women. So how on earth did this happen?

Well, it turns out that this study was not even remotely comparing like with like. While all participants are described as amateur volleyball players, the male and female participants are vastly different.

The female athletes are 5 centimetres taller - averaging around 5’10” - and 7kg heavier than their trans-identifying male counterparts, and train almost 10 hours per week more. These are women in the top 0.5% being compared to men of average height and well below average weight. While these men recorded a grip strength of 34.4kg, the women were far stronger, clocking in at 39.3kg. Indeed, describing all the participants as “amateur” players doesn’t do justice to the fact that - unlike the men who participated at the state and city level - the women in question competed in “second division national level championships”. This is a huge difference in sporting prowess, and - since the first division in Brazil is the elite professional league - is pretty much as high as you can go in volleyball as an amateur.

Another interesting detail from this paper:

Volleyball team organisers (made up of TW) sought out our research centre. They suggested an assessment of the sports capabilities of this population and the possibility of disseminating the research opportunity to other athletes.

That is, this research was directly instigated by trans-identifying males with a vested interest in participating in female sport. There is a perverse incentive for these participants to not try their hardest, knowing that if they demonstrate high grip strength this provides evidence against their inclusion. This introduces massive selection bias - participants who know that underperforming could influence policy in their favour have a significant conflict of interest.

There are techniques for ensuring such tests are engaging in maximum effort, but the paper does not detail whether any such methods were used, and no mention of this possible confounding factor appears in their conclusions, which would seem to be a significant oversight.

In the supplemental material of this latest systematic review, the authors note that there are confounding variables with Alvares et al (2025), and give a different set of values calculated only from the other three studies, which are 0.89 (-0.04; 1.81), 22.7%

So if they exclude just that one paper, they found a strong difference in grip strength (nearly one standard deviation) and with far less differences between the papers to account for errors. These are still not statistically significant, but just barely, and clearly suggests that there is indeed a strength differential - and the heterogeneity of these studies is far better (less than 25% as opposed to over 75% when Alvares et al 2025 is included)

So: the authors have taken studies that compared untrained men with supremely athletic women, self-report activity, under-20s with over-30s, less active men than women, matched controls, hormonal interventions from 0-24 years, grip strength recorded four different ways with no reported verification of maximal effort, and mixed them all together into a single nonsensical result.

In short, they have taken a mess of ingredients and made a beef trifle.

While it is true that a systematic review typically has to deal with some level of differences between studies, the fact that across four studies they achieved a heterogeneity figure of over 75% - and that this was overwhelmingly due to one obvious and implausible outlier study - should have been a big indication that there are simply too many differences to mix these together and produce a palatable result.

Yet that is what has happened - incompatible ingredients served up on a plate, while a chorus of partisan commentators insist that we choke down this tasty dish that’s been placed in front of us. Swallow this with a smile, or you’re a bad person.

I have only looked at grip strength in this systematic review, but it covers multiple other variables, from lean mass, to VO2 max, and over and over again, Alvares et al (2025) is an outlier, destroying the statistical significance of other findings and driving up the heterogeneity:

By my reading:

Alvares et al (2025) is useless and should not have been included as the cohorts are wildly different

Ceolin et al (2024) is baseline, pre-intervention numbers and should not have been directly compared to post-intervention studies

Ceolin et al (2024b) is a one-year followup and it is unclear why it wasn’t included

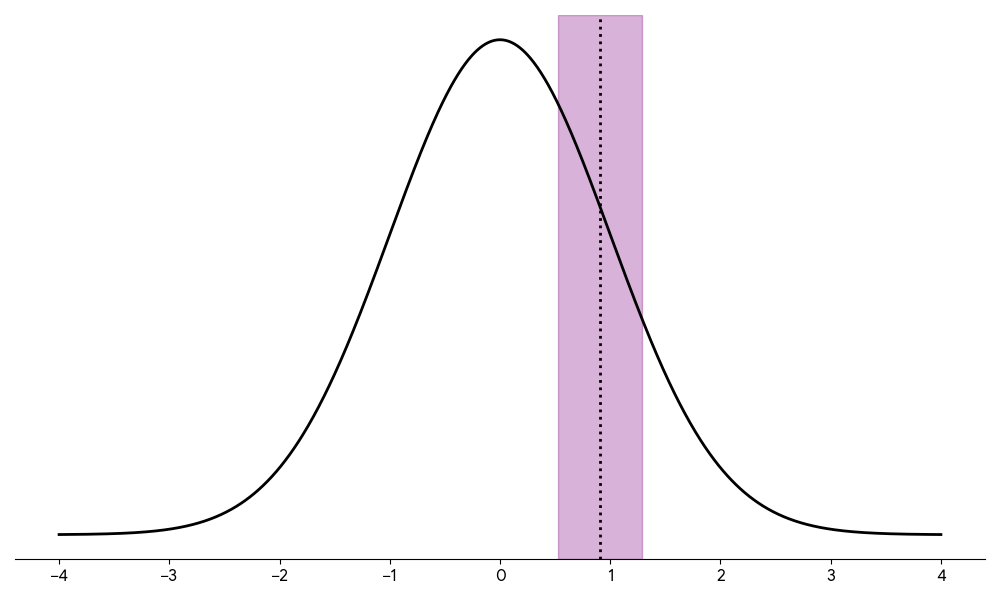

Calculating the grip strength differential from Alvares (2022), Hamilton (2024) and Ceolin (2024b) produces a large, highly statistically significant strength advantage for men despite >1 year of cross-sex hormones: 0.91 (0.53 to 1.29)

In the fractious ongoing cultural battles over sex and gender, science has become a key battleground, with different factions trumpeting their own pet scientific papers as definitive. In that environment, systematic reviews are supposed to represent the gold standard, providing an objective, neutral assessment of the entire state of the literature.

What has happened here is:

A team of researchers at São Paulo University conducted research at the request of men with a vested interest in being included in female sports, which compared below-average men with low grip strength to national-level female athletes in the top 1% of female performance.

Another team of researchers at São Paulo University included this in a systematic review and - instead of dropping it because of the clear methodological issues and confounding factors - combined it with multiple other studies that can’t be directly compared, and produced a result so incoherent as to be meaningless.

Then, they declared in their conclusion that because they had a meaningless result they had found an “absence of strength disparities”, while arguing their research was evidence against “blanket bans”.

This was then published by the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

This was immediately picked up and circulated widely - from news outlets to Wikipedia - as clear evidence that male athletes given cross-sex hormones do not have a performance advantage against female athletes, and thus should not be subject to blanket bans.

The systematic review’s conclusion that there is a lack of strength disparities and that this has implications for sports policy is based on statistically untenable foundations. While I tend to give short shrift to those on the sidelines who cry foul about science that is inconvenient to their political aims, it really does seem that the chain of trust in science has been seriously damaged by activism and groupthink in the area of sex and gender. From paediatric gender medicine to sports science, badly designed studies and papers with obvious issues are being waved through by compliant journals, and shoddy, meaningless results spun as triumphs by political partisans. These generate exactly the expected headlines, which translate into pressure on institutions and political leaders. We need to be able to rely on the scientific method to provide us with a dispassionate and neutral assessment of the evidence which rises above such blatant policy advocacy.